Notes from "Where is my Flying Car?"

A book by J. Storrs Hall, published by Stripe Press in November 2021

Note: This post presents a review/summary of some select points from this book that stood out to me personally. A much more thorough review by Rohit at Strange Loop Cannon can be found here. There’s also an excellent podcast discussion about the book between Rohit and Dwarkesh Patel that you can listen to here or watch on YouTube.

Readers of this blog are most likely already familiar with The Great Stagnation thesis. Named after a 2011 book of the same name by Tyler Cowen, it is based off the observation that many economic metrics started to stagnate in the early 1970s. The most oft-cited metric is median wages, but the stagnation shows up in a surprisingly large number of other metrics as well. The causes of The Great Stagnation and what we can do to get ourselves out of it is the subject of much discussion within the Progress Studies community.

J. Storrs Hall’s book Where is my Flying Car?, recently published by Strip Press, explores why we don’t yet have flying cars and uses the answers he finds as launching off points for a broader discussion on the causes of The Great Stagnation. This book is about much more than flying cars. More broadly, this is a book about how the future could be even more glorious than what was envisioned in the 1960s, how we lost our way, and how we might get back on the path to a grander future.

John “Josh” Storrs Hall is a long-standing and well-known figure within the futurist community. A computer scientist by training, he is also well-versed in engineering, demonstrating an impressive grasp and command of aerodynamics, nanotechnology, and physics in the book. Among his many accomplishments he founded the sci.nanotech Usenet newsgroup, served as President of the Foresight Institute between 2009-2010, and was appointed a research fellow at the Institute for Molecular Manufacturing.

The hippies

“Men reached the moon in July 1969, and Woodstock began three weeks later. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that this was when the hippies took over the country, and when the true cultural war over Progress was lost.” - Peter A. Thiel, “The End of the Future”, 2011.

Following Thiel, Hall also believes that the hippie movement played a role in causing The Great Stagnation. At the highest level, the story here is a classic one of cultural decadence and decay. The post-war boom led to a generation that was more spoiled than any that came before. Humans, however, are not just content to be lazy once their material needs are met — people seek purpose to satisfy their self-esteem and achieve self-actualization. Earlier generations had a much more unified sense of purpose as they came together to preserve their civilization through two world wars and The Great Depression. Not having a major cause to rally around, the Hippies broke off into myriad splinter movements, especially after the end of the Vietnam war in 1975. These included environmentalism, free love, pacifism, feminism, and numerous new age cults and religious groups. Additionally, in a pattern that continues to this day, people started inventing “crises” out of problems that were smaller and smaller. In other words, as people become more and more spoiled, they also became more and more prone to magnify the scope of crises that were in need of solving. Hall calls these hippies the “Eloi agonistes” after the Eloi, the lazy far future humans in H. G. Well’s The Time Machine who live in a utopian garden (“agonistes”, on the other hand, refers to people who are engaged in a struggle). In explaining The Great Stagnation, Hall places high importance on rise of the “Eloi agonistes”, which bears some resemblance to Tyler Cowen’s “Complacent Class”.

Storrs Hall states:

“A substantial number of the expected but unattained technological advances were not mispredictions of technology. They were instead misplaced faith in the vitality and dynamism of our culture, and in the wisdom, and indeed, the basic competence of our information providers and systems of governance. We poured increasing torrents of money into the ivory tower and virtue signaling, and it increasingly took our best and brightest away from improving our lives…”

“Imagine that the best and brightest of my classmates had spent their time studying instead of protesting, working out new inventions together instead of getting stoned together, and had gone on to become engineers instead of activists, regulators, and lawyers.”

Unlike other parts of the book, which are grounded in hard science, this part is admittably more of a qualitative argument, and thus more questionable.

Energy

The hippies may be mostly gone now, but we bear much of their cultural legacy, both good and bad. For instance, the anti-nuclear power movement is a direct outgrowth of the Hippies’ anti nuclear-weapons movement. Hall claims that to this day 66% of people believe that a nuclear power plant can explode like a nuclear bomb - a particularly devastating bit of misinformation that was promulgated by hippy-era environmentalists. Another cultural legacy from hippy environmentalists Hall talks about is “ergophobia” — the fear of energy production. Around 1970 energy use per capital, which he calls the “Henry Adams curve”, flat-lined:

In 1954 the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission famously predicted that within 15 years electricity would be “too cheap to meter”. At that time the prediction was not so outlandish as it seems now. Many types of nuclear power plant had already been demonstrated, such as the experimental breeder reactor EBR-1, which had been running for three years. [Breeder reactors like EBR-1 generate (“breed”) their own fuel and produce 100x less nuclear waste than conventional Uranium reactors but sadly were never commercialized.]

Unfortunately, the development of nuclear technology stagnated in the 1970s. The NERVA nuclear rocket was tested between 1968-1969. [With the signing of international treaties, launching a nuclear rocket from the surface of the Earth was effectively banned, but the NERVA program continued to explore uses for interplanetary flight for a few decades before being shut down.] Hall also discusses nuclear batteries such as Betacel, which was commercially produced in the 1970s and for a short time was used in pacemakers. The physics behind betavoltaic batteries, which use beta rays (high energy electrons) is quite straightforward and no nuclear fission is involved. With current day technology, betavoltaic batteries have about 50 times the energy density of chemical batteries (although the current batteries are pretty limited in how much current they can produce). One can start to understand why Asimov had predicted in 1964 that “the appliances of 2014 will have no electric cords”. Ironically, a properly constructed betavoltaic battery is safer than today’s lithium ion batteries, which are known to explode and violently catch on fire if bent or punctured. People are deathly afraid of even tiny risks of small amounts of radiation leaking out but have no problem with chemical batteries loaded with toxic metals like lithium, cadmium, nickel, and even mercury.

Hall peppers his discussion with interesting factoids such as the fact that a half ounce of Thorium contains as much energy as 60,000 pounds of gasoline, or that the seabed has so much Uranium lying on it that it’s equivalent to if it were made of solid coal. Hall argues that nuclear technology could have provided us with cheap and abundant energy and made spaceflight and flying cars a lot more economical and feasible. This is not even to mention fusion, which Hall discusses as well. More specifically, Hall advocates for renewing research into cold fusion. He doesn’t make a strong claim that cold fusion is a real phenomena but argues that research on it was passed over too quickly by funding agencies. Hall points out that lack of cheap energy, rather than radiation, is the real and present danger. Citing an NBER report he claims that 28,000 US residents die each year from cold, mostly poor people who can’t afford to properly heat their homes (the actual number appears to be closer to 10,000).

Hall also discusses the Nuclear Regulatory Agency, which was founded in 1975. New nuclear plants have been built since the NRC was founded, but construction costs exploded dramatically after it was founded - rising 7x between 1980 and 1995. Patrick Collison, CEO of Stripe Press, pointed out on Twitter recently that all of the new plants that have been built were using construction permits obtained before the NRC was formed. In other words, no new nuclear construction permits have been granted since the NRC was created. Meanwhile, the Navy, which is not under the auspices of the NRC has built many nuclear-powered submarines and run them for years without any major incidents.

Hall also points out that the number of people getting Ph.Ds. in nuclear physics in the US peaked around 1973 and has been falling since. Hall points out, correctly, that there there is still no unified theory for understanding nuclear phenomena, equivalent to the atomic model for understand atoms and chemistry. Nuclear structure is still poorly understood and nucleon interactions are studied using approximate lattice QCD simulations and can’t be predicted on the basis of a unifying theory or set of principles. There are many open problems in nuclear theory, but the area is not considered cool by graduate students today.

Overall, the picture Hall paints with nuclear technology is quite depressing and it is here, in my opinion, that the gap between what is clearly possible and what we’ve actually done is the most striking.

Flying cars

The development of airplanes generally stagnated in the late 1960s - the types of aircraft we use today are not much different than what we had then (The Boeing 747 was first introduced in 1969). Commercial airline cruising speed hit a plateau in 1960 with the exception of the short-lived Concord jet.

The book contains detailed analyses of different flying car designs and how economically valuable they would be, using results from a branch of economics called “travel theory”. Though detailed engineering analyses, Hall shows how how many types of economically valuable private aircraft and flying cars are entirely possible even with 1950s technology.

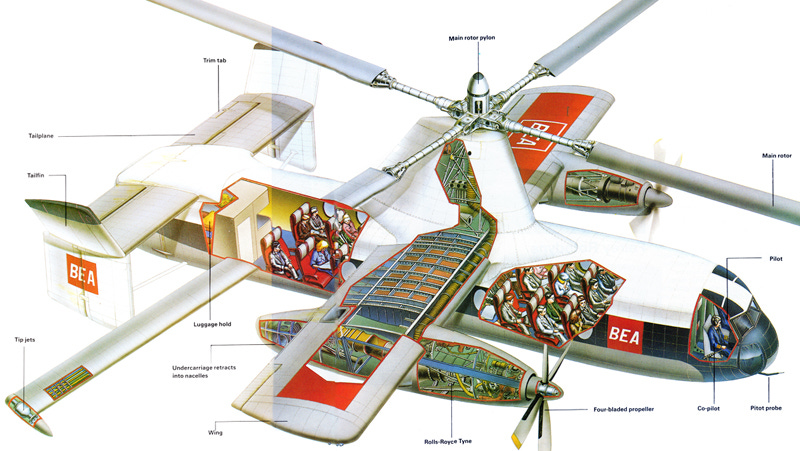

Private aeroplanes were very much in the ascendancy in the 1930s and 40s. The autogyro, which is a cross between a plane and a helicopter, is virtually unknown today — I had not head of it until reading this book. Yet in the 1930s Pitcairn was selling their PCA-2 autogyro for $5,000 (about $105,000 in today’s dollars). Autogyros are remarkable because they can take off and land on a small patch of land (about 50x50 m) and are easier to fly than a helicopter. To take off, a motor spins the horizontal rotor, but for the rest of the flight the rotor spins freely “autorotation”. Reading about autogyro technology in the book led me to do a bit of research online where I discovered the Rotodyne, a large “gyroplane" capable of taking off and landing from a rooftop (there is a good video on YouTube about it). It sported a top speed of 213 mph and a range of 450 miles. Imagine getting into one of these on the top of a Manhattan skyscraper and then flying directly to Boston!

As Hall explains in the book, there are some challenges with autogyros, most notably noise and the need for expensive precisely machined parts and bearings. However, Hall believes autogyros could have been developed much further than they were. Hall points to the rise of tort law in the 1950s that made liability costs for private aeroplanes extremely expensive. By the 1960s the private aeroplane industry had completely collapsed, and with it the development of the flying car. Only a few thousand private airplanes are sold each year today.

A true flying car, of course, is not just a private airplane but can also serve as a ground car, ideally with a small take-off and landing footprint. The book contains a number of detailed analyses of different approaches to building flying cars and their pros and cons. These sections are quite technical and difficult to summarize. Hall, who is an amateur pilot, also analyzes how difficult it would be for a person to learn how to fly a flying car (it is rather tricky) and how hard it would be to coordinate many cars in the sky (easy — there is lots of space in three dimensions and we can use GPS and onboard radio beacons).

Nanotech

Many people know that the field of nanotechnology was sort of inaugurated by a famous lecture by Richard Feynman entitled “There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom" that he gave at Caltech on December 29th, 1959. There are no recordings or transcripts of that lecture, but the ideas were so new and bold they immediately caused quite a great stir. Among the ideas proposed, Feynman proposed building a miniature set of robotic arms which would be slaved to an teleoperator’s arms. Those arms could then be used to build a smaller pair of arms, which would build a smaller set of arms, and so forth until the molecular scale was reached. 10 four-fold reductions in size leads to a million-fold reduction, from millimeters to nanometers.

The ultimate goal of nanotech, as Feynman conceived it, was to build molecular machines. While nanotech has borne much fruit, such as better materials and the lipid nanoparticles used in the mRNA vaccines, the “Feynman path” to molecular machines was never seriously pursued. More generally, very little money has been invested directly into building self-replicating molecular machines for atomically-precise manufacturing, the holy grail of nanotechnology. According to Hall, this is because what he calls “the Machiavelli effect” whereby established academics shoot down new research directions that threaten the status quo. In the case of nanotechnology, established researchers in chemistry and materials science slightly pivoted in their work and rebranded it as “nanotechnology” to secure funding. The National Nanotechnology Initiative was founded in 2000 and between 2001-2015 the NNI has invested $21 billion. Many great discoveries and inventions have come out of this investment, but very little of this money was actually put towards the more ambitious and truly revolutionary technologies like building self-replicating nanomachines and atomically-precise nano-assemblers.

Academia

The book contains many rousing heterodox takes, some of which are not super well justified. For instance, citing arguments from Terrance Kealey and some cherry-picked statistics, Hall casts skepticism on whether public funding of R&D helps boost economic growth. He also argues that the creation of more Ph.Ds. has contributed to The Great Stagnation. I agree with Hall that for many doing a Ph.D. is a waste of what would otherwise be their most free and productive years, but it’s not clear if this is a big enough problem to have substantially contributed to The Great Stagnation. Hall excoriates the academic establishment, saying:

“Academia is more interested in ‘mind candy’, intellectual tricks that impress other intellectuals .. as contrasted with mundane techniques that just happen to work and do something useful".

Conclusion

The book concludes with an engineer’s dreams of the future. Hall envisions airplanes with 10 miles long wings, cities with multiple levels of streets, and even larger projects such as floating cities, space piers, ten mile high towers, and weather control systems. Most of these are only become feasible with nano-assemblers and fully developed nanotechnology. If you like really hard science fiction, you’ll love this part of the book.

A popular explanation for The Great Stagnation is that we “picked all the low-hanging fruit”. Hall rejects this outright. In his view, we could have had flying cars, clean energy too cheap to meter, molecular nanotech, and vacations on the rings of Saturn by now had we acted differently. In his view, we have become lazy, unimaginative, and too risk adverse, suffering from what he calls “failures of imagination” and “failures of nerve”. This cultural malaise has been locked-in by the creation of regulatory bureaucracies and the ascension of myopic status-quo oriented leadership in centralized government funding agencies. Whether you agree or not with Hall’s bold theses, the book still makes a very compelling case for being more ambitious by presenting very detailed descriptions about what technologies could be within our grasp, if only we can find collective will.

The book ends with this quote, which I also think is a fitting way to end this post:

“It is not really necessary to look too far into the future; we see enough already to be certain it will be magnificent. Only let us hurry and open the roads.” - Wilbur Wright

Great article. Nice read with my morning coffee. Howard (Toronto).

“ More specifically, Hall advocates for renewing research into cold fusion. He doesn’t make a strong claim that cold fusion is a real phenomena but argues that research on it was passed over too quickly by funding agencies.”

This is the real red flag to not take the book’s author seriously.