All of these things about COVID-19 can be true (this is scary)

The following can all be true at once about COVID-19:

➡️ Getting COVID-19 now feels like getting the flu or less, for almost everyone.

A very carefully conducted study published in JAMA in 2022 compared the time course of symptoms experienced by COVID-19 patients with COVID-19 negative patients who had an upper respiratory tract infection. The two groups were statistically indistinguishable in terms of their symptom burden and time course. Interestingly, the study found both groups had 20-30% reporting symptoms after three months. (There was no ‘no-disease’ control group, so a lot of that is just a background rate.) It’s important to point out that this study did not look for differences in symptom burden lasting longer than three months, and it was likely not powered to do so. That brings me to my next point:

➡️ About 5-10% of people will get some form of Long COVID for a year or longer. About ~2% will have life-deranging illness for a year or longer.

Having a symptom longer than three months is considered the threshold for “Long COVID” by most researchers. Many studies now show that about 30% of people will have at least one persistent symptom for three months. Fatigue for six months or longer is the typical threshold used for diagnosing “chronic fatigue syndrome.” The number of people experiencing one or more symptoms for 6 months or longer is about 10%. After that there is a long tail. About 5-10% will have a persistent symptom for a year or longer. I would guess that about ~2% will have life-deranging illness for a year or longer (ie completely unable to work, greatly reduced activity levels, chronic fatigue and brain fog, etc.) Many of these people will suffer enormously, both psychologically and physically. Since COVID-19 just started in 2020, we don’t have much data on recovery rates from Long COVID. However, if we look at recovery from glandular fever (mono) or chronic fatigue syndrome more generally, what we find is that the percent recovering each year decreases over time. This decreasing recovery rate results in a long-tail of patients who are stuck with the illness for a very long time (years or decades). If Long COVID is similar to post-viral syndromes generally then we might expect the fraction recovering between years 1 and 2 to be 20%. Thus, we can infer that about 4% will have some form of Long COVID for two years, and 3% will have some form for five years or longer. The exact number is not that important. Even 1% is a big deal. (addendum: a 2023 survey by Jake Skarbinski found 0.5% of people who have had COVID have developed long term chronic fatigue which started after COVID).

➡️ Every COVID-19 infection can cause brain damage and small long-lasting or permanent drops in IQ.

What worries me here is small drops in IQ that people don’t notice. There is emerging evidence that even mild COVID-19 can have long-lasting effects on the brain - damaging the blood-brain barrier and leading to subtle deficits in memory and cognition. See the first appendix for a detailed summary of the literature.

➡️ Every COVID-19 infection may cause long-term weakening of people’s immune systems, leaving them more susceptible to getting COVID-19 and other illnesses in the future (this is speculative, but possible.)

The evidence for this right now is weak, but from what I have read, many doctors are worried about the possibility. A paper from 2020 reported that COVID-19 triggers “T cell exhaustion” in both hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients, resulting in “long-term immune dysfunction.” A March 2023 paper in Immunity found “a major reduction in both the magnitude and functionality of peak CD8+ T cell responses in previously infected individuals after vaccination.” The authors note that this is similar to what is seen in diseases like HIV. What they found is that people who have had COVID-19 are less able to mount a proper response to vaccination compared to COVID-19 naive controls. Another paper published in August 2023 in Cell found changes in the immune system that lasted over a year. Apparently COVID-19 can trigger epigenetic changes in the stem cells that form new immune cells. Unfortunately these epigenetic alterations are inherited by the next crop of stem cells. The result is persistently elevated production of white blood cells together with more cytokines (such as IL-6) being spewed out, causing higher systemic inflammation. While this is not a weakening of the immune system (it actually looks like a persistent strengthening), it doesn’t sound good. The bottom line is that COVID-19 appears to be causing long-lasting immune dysfunction in some individuals.

Minor update 3/19/25 — see also this paper in Scientific Reports from April 29, 2024 which found lower immune response in Long COVID patients.

COVID-19 is sticking around..

When the WHO declared "the pandemic is over" last May almost everyone took that as a sign that it was safe to return to how they lived before. (CORRECTION - technically what the WHO announced was the end of the “Public Health Emergency of International Concern”). The narrative shifted immediately overnight - COVID-19 moved from “pandemic” to “endemic.” Behavioural patterns quickly jumped back to how they were in the “before times.” Nobody masks and when people get sick they don’t quarantine for very long.

The idea that "COVID is just like the flu", which was once only popular on the right, has become mainstream. It goes without saying that this statement is simply not true. The flu does not cause “long flu” at the rate that SARS-CoV-2 causes Long COVID. SARS-CoV-2 is also far more infectious than the flu virus. Severe COVID-19 also looks a lot different than severe flu.

Many people also assume that the COVID-19 virus is getting weaker over time. From an outside perspective, we should expect SARS-CoV-2 to evolve to be weaker over time based on what has been seen with other viruses. Famously, the H1N1 virus that caused the 1918 flu evolved into weaker strains that still make up a small fraction of the seasonal flu today.

However, studies do not show the virus evolving to become weaker in the past two years or so. The average case of COVID-19 today is less severe, but that is only because of vaccination and prior immunity, not because the virus itself is less dangerous.

The stark reality we must face is that the overall burden of COVID is not decreasing. (By “burden” I mean the integration of symptoms over time and people.)

Antibodies (whether from infection or from vaccines) don’t last very long, and the virus is quickly evolving. People are not getting boosters. So it’s even plausible that the overall burden of COVID-19 may actually increase in the next few years.

Let’s look at this in more detail:

➡️ Wastewater data shows the exact same viral load patterns as last year.

We can observe this on both the CDC’s national platform and local monitoring platforms like the Boston-area one. What this indicates is that collectively the amount of SARS-CoV-2 virus that is ravaging our bodies is not decreasing. Also, the last big wave of COVID-19 this January overwhelmed the Massachusetts General Hospital as well as some other hospitals. This was barely reported in the news compared to the reporting in the previous two cycles.

➡️ Death rates from COVID-19 in 2024 are only slightly less than 2023.

See the New York Times dashboard (they are one of the few places that still have a functional dashboard.) You would think that with boosters and the miracle drug Paxlovid that death rates would be down more. In addition, 1.2 million Americans have already died (we should expect the weakest to die first), and the reporting standards for COVID-19 deaths have declined.

➡️ Rates of Long COVID are not declining and actually just ticked up slightly.

Data from the CDC shows that in mid 2022 the fraction of Americans experiencing Long COVID was around 7%. This number decreased somewhat to around 5.5% in 2023 but recently increased up to 6.8%. Studies show that an individual’s risk of getting Long COVID increases with every subsequent infection. With fewer people getting boosters and better immune evasion in the latest variants more people are experiencing reinfections. So maybe we shouldn’t be surprised that Long COVID rates just increased.

➡️ The virus doesn’t seem to be becoming weaker.

Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) binding correlates with both disease severity and transmissibility. The first major variant, Alpha, had stronger ACE-2 binding according to assays. Subsequent work shows that the Delta variant had weaker ACE-2 binding compared to Alpha but still was stronger than the original strain. Understanding Omicron is complicated due to the large number of subvariants. Early data in mice suggested that the early Omicron variant was weaker than Delta. However, more recent variants of Omicron have had stronger ACE-2 binding. The Omicron BA.2.86 variant which emerged last summer has increased ACE2 binding, increased antibody evasion, and comparable lung cell entry rate compared to the earlier Omicron BA.2. Similarly, one study reports that Omicron BA.2.75 had the “strongest ACE-2 affinity of any variant to date.” A descendant of Omicron B.2.86 called JN.1 started to achieve dominance in early 2024. While early evidence suggested it was more severe, the CDC now thinks it is “not any worse” than previous strains. My overall read on all this is that 1. the virus is definitely learning how to spread faster and better evade prior immunity and 2. the severity/strength of the virus is fluctuating with no overall trend that is easily discernible. (Again, “severity” means how bad the disease is for unvaccinated individuals with no prior immunity.)

➡️ Scientists are struggling to keep up with the virus’s evolution.

Right now there is a lot of debate about why JN.1 is spreading so fast. Initially people thought it must be escaping the immune system better, but recent work indicates this not to be the case. Something is happening with JN.1 and scientists have yet to figure out what it is.

Coronaviruses have been found to exhibit viral recombination. During recombination, RNA fragments from two or more different variants combine to create a new variant. This process allows the virus to evolve faster, which is scary.

COVID-19 denialism and the future of humanity

It’s fair to say that most of the world is in a state of denial about COVID-19.

Wastewater COVID levels remain just as high as last year and 23 million Americans are experiencing Long COVID. The virus continues to evolve rapidly and is constantly finding new ways to avoid immunity.

For most people, getting COVID-19 may mean a week or two of sickness followed by a small amount of long-term damage (essentially accelerated aging.) However, a small fraction of people are having long-term effects.

I know several people who have had COVID-19 three times and one of my coworkers has had COVID-19 five times. My concern is the cumulative toll that takes on our bodies and brains.

Just a three point downward shift in IQ in the United States would increase the number of adults with an IQ less than 70 by 2.8 million. It would also dramatically lower the number of geniuses (IQ > 145), which could have an effect on progress in science and technology.

This is speculative, but there appears to be a tail risk here that involves long-term enfeeblement of our species.

What should we be doing in response to all this? Well, hardening infrastructure with air filtration and UV-C. Developing better masks. Massive investments in research on the long-term health effects of COVID-19 and how to treat them. Development of better vaccines (pan coronavirus vaccines, nasal vaccines). Probably many other things — let me know in the comments!

Appendix - the research on the cognitive effects of COVID-19

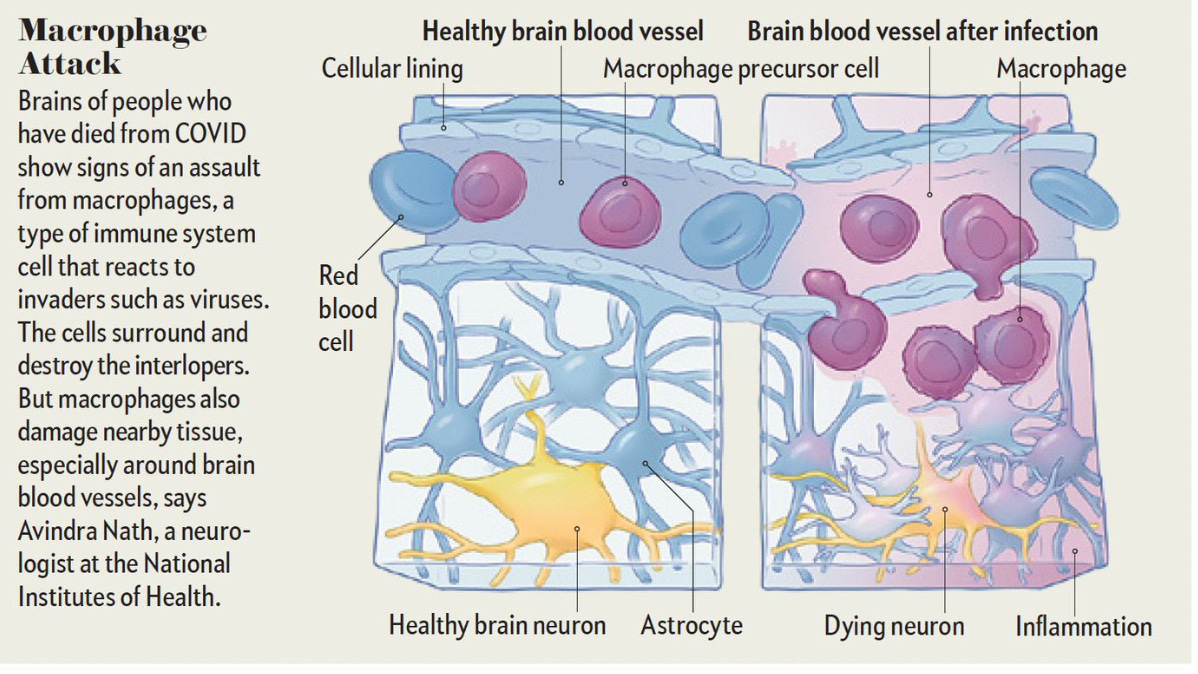

I think it’s worth discussing the plausible mechanisms first. In severe COVID-19, coagulation, vascular injury, hypoxia, and large fluctuations in blood sodium can all cause immediate and permanent brain damage. A figure from Scientific American talks about how during severe COVID-19 macrophages in blood vessels can damage the brain:

In mild or moderate COVID-19 several mechanisms have been postulated:

One widely discussed possibility is direct infiltration of the virus into the brain. While bits of SARS-CoV-2 virus have been found in the brain in autopsy studies, it seems to be quite rare. One of the ways the virus is thought to get into the brain is through the nose. Anosmia (loss of smell) indicates a high viral load in the nose and indicates a higher risk for brain infiltration. If the virus does get into the brain it’s very bad news. Research in human brain organoids shows that the virus can trigger fusion of neurons and glia cells, which disrupts brain function.

The next way brain damage may occur is through inflammatory cytokines. Neuroinflammation has long been thought to be the cause of the poorly understood symptom called “brain fog” which is one of the most commonly reported and longest persisting symptoms of COVID-19. Cytokines activate immune cells called microglia in the brain. The microglia go into “overdrive”, producing large amounts of reactive oxygen species and more pro-inflammatory cytokines. The cytokine CCL11 is of particular note because it has been observed to be greatly elevated during COVID-19. Animal studies show that CCL11 reduces neurogenesis and triggers the loss of oligodendrocytes, which form the important myelin sheaths around axons. A study that looked at mice and human autopsies found clear signs of both microglia activation and loss of oligodendrocytes after COVID-19.

Next is damage to the blood-brain barrier. A recent study in Long COVID patients shows clear evidence of blood-brain barrier damage. My understanding is that once this damage occurs it is very hard to repair. It goes without saying that a leaky blood-brain barrier means that toxins can more easily enter the brain. A leaky blood-brain barrier has been linked to multiple sclerosis, dementia, Alzheimers, psychosis, and epilepsy. Is this is sort of damage occurring in regular mild cases of COVID-19? I would guess it probably is, but to a lesser degree that what is seen in Long COVID patients.

Finally, it is widely hypothesized that the inactivation of the ACE-2 receptor by the SARS-CoV-2 virus may reduce brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and have other negative effects on the brain. There is already some convincing-looking evidence for this effect in humans. ACE-2 blocking can also mess with serotonin synthesis and increase stress and anxiety. While the ACE-2 receptor is mainly known for being expressed in abdominal organs and the heart, it is also expressed in neurons, especially in the hippocampus. I would guess that the effects of ACE-2 blocking are temporary, and go away once the virus is cleared, but recall that the virus can persist in the body for quite some time.

So, what evidence is there that COVID-19 can have long-term consequences on the brain? It’s tough to summarize the literature in a short space. Not surprisingly I found recent media reports do a somewhat sloppy job. The first thing I look at in any study is the patient population. Some studies look at severe COVID-19 (I’ve ignored those below), while others look at elderly populations or populations with Long COVID. Only recently have there been studies that look at younger populations and/or populations who had mild COVID-19. All of the studies I looked at are listed in the Appendix, and to save space not all are discussed here.

The best evidence is in studies on elderly populations. A large study on older patients in the UK Biobank showed brain alterations and evidence of cognitive decline. Data from the Veterans Administration in the US show a similar effect. A meta-analysis of 11 studies looking at older adults concluded that getting COVID-19 nearly doubles the risk of “new onset dementia” after 12 months. This is consistent with a wide body of emerging research showing that some viral infections are implicated in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Other culprits of note are cytomegalovirus, HIV, varicela zoster virus, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), and the hepatitis C virus.

The next best evidence for brain alterations due to COVID-19 is in populations with Long COVID. When I first looked at the literature on Long COVID and brain damage in 2022 I found several MRI/fMRI studies with mixed results - some studies found evidence of brain damage while others found none. Now a somewhat clearer picture is emerging and overall it isn’t good news for those with Long COVID. In patients with Long COVID (illness > 3 months) the ongoing IQ loss appears to be about 6 IQ points on average.

What about healthy younger people who have mild COVID-19? This is still an emerging area of research. A very large observational study suggests small cognitive deficits that persist for a year or more and scale up with illness duration. One study of 54 healthy individuals between 18-54 who had COVID-19 found lower performance on cognitive tests. A survey of 188,137 Norwegians found a small decrease in reported memory function after COVID-19 that persisted up to 36 months.

Appendix - the studies on cognitive effects

Vavougios, George D., et al. “Investigating the Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment in Mild and Moderate COVID‐19 Patients Two Months Post‐discharge: Associations with Physical Fitness and Respiratory Function.” Alzheimer’s & Dementia, vol. 17, no. S6, Dec. 2021, p. e057752.

Zamponi, Hernan P., et al. “Olfactory Dysfunction and Chronic Cognitive Impairment Following SARS‐CoV‐2 Infection in a Sample of Older Adults from the Andes Mountains of Argentina.” Alzheimer’s & Dementia, vol. 17, no. S6, Dec. 2021, p. e057897.

Douaud, Gwenaëlle, et al. “SARS-CoV-2 Is Associated with Changes in Brain Structure in UK Biobank.” Nature, vol. 604, no. 7907, Apr. 2022.

This much-publicized paper looks at structural MRI images of 785 people in the UK Biobank. They claim to find reductions in grey matter thickness in certain regions as well as a reduction in ‘global brain size’. They also found cognitive decline on something called the “Trail Making Test”, a simple test that asks participants to connect dots as quickly as possible. The study only looked at people age 51 - 81 years and the cognitive decline was almost non-existent for those around 50 and increased with age.

Holdsworth, David A., et al. “Comprehensive Clinical Assessment Identifies Specific Neurocognitive Deficits in Working-Age Patients with Long-COVID.” PLOS ONE, vol. 17, no. 6, June 2022, p. e0267392.

Fernández-Castañeda, Anthony, et al. “Mild Respiratory COVID Can Cause Multi-Lineage Neural Cell and Myelin Dysregulation.” Cell, vol. 185, no. 14, July 2022, pp. 2452-2468.e16.

This work was a combination of a mouse study and an autopsy study. Strikingly, clear differences were seen in brain micrographs between COVID-19 patients and controls. They find evidence of increased microglial activity, and loss of myelination. As discussed above, the cytokine CCL11 is pointed to as the culprit.

Wang, Lindsey, et al. “Association of COVID-19 with New-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease.” Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, vol. 89, no. 2, Sept. 2022, pp. 411–14.

This was a simple retrospective cohort study of 6,245,282 older adults (age ≥65 years) who had medical encounters between 2/2020–5/2021. They found an increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis within 360 days of COVID-19 diagnosis (hazard ratio = 1.69.)

Xu, Evan, et al. “Long-Term Neurologic Outcomes of COVID-19.” Nature Medicine, vol. 28, no. 11, Nov. 2022, pp. 2406–15.

This study looks at Veterans Affairs data with ~150,000 COVID-19 patients and finds a somewhat increased risk for “neurologic sequela” in the first year after COVID-19 (hazard ratio 1.42.) Limitations of this study are its observational nature and limited correction for confounds.

De Paula, Jonas Jardim, et al. “Selective Visuoconstructional Impairment Following Mild COVID-19 with Inflammatory and Neuroimaging Correlation Findings.” Molecular Psychiatry, vol. 28, no. 2, Feb. 2023, pp. 553–63.

This study looked at 192 people who had COVID-19 (71% female.) The sample was relatively young (average age 38 years.) Only 6% were hospitalized. 64% had anosmia, which is interesting and potentially a source of bias in this sample. About 25% of the patients had a “visuoconstructive deficit” which is a deficit in a very particular type of cognition - arranging objects spatially (“deficit” is defined as being 1.5 std below average, which we expect to normally be about 3.3%.) I haven’t done a detailed analysis of the stats but this study looks p-hacked to me.

Petersen, Marvin, et al. “Brain Imaging and Neuropsychological Assessment of Individuals Recovered from a Mild to Moderate SARS-CoV-2 Infection.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 120, no. 22, May 2023, p. e2217232120.

This study was mostly negative findings, although that is not what was reported in outlets like Scientific American. They looked at 223 unvaccinated individuals who had “mild to moderate” COVID-19 and 223 matched controls. Most patients were around 40 - 60 years old. They found two statistically significant MRI biomarkers tested out a total of 20 (with corrections for p-hacking applied.) Notably, they did not find any difference in neuropsychological test scores. What they found is “subtle changes in white matter extracellular water content.” They say this “relates” to approximately 7 years of “healthy aging.” They say “microglia and astrocytes emit cytokines upon activation, inducing osmosis of water from the blood into the extracellular space.” While this work needs to be replicated, I think it is significant given the amount of time that had passed after infection in these patients (range was 163 - 318 days, mean 289 days.)

Martínez-Mármol, Ramón, et al. “SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Viral Fusogens Cause Neuronal and Glial Fusion That Compromises Neuronal Activity.” Science Advances, vol. 9, no. 23, June 2023, pg. 2248.

This was a study on human and mouse brain organoids. They show that SARS-CoV-2 infection causes “fusion between nuerons and glia” which “compromises neuronal activity.”Demir, Biçem, et al. “Long-Lasting Cognitive Effects of COVID-19: Is There a Role of BDNF?” European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, vol. 273, no. 6, Sept. 2023, pp. 1339–47.

This study looked at 54 individuals between ages 18-50 who had gotten mild COVID-19 within a six month window. They found lower BDNF and lower performance on a digit span test compared to a control group. I’m surprised this one has not been more widely reported.

(PREPRINT) Michael, Benedict, et al. Post-COVID Cognitive Deficits at One Year Are Global and Associated with Elevated Brain Injury Markers and Grey Matter Volume Reduction: National Prospective Study. In Review, 5 Jan. 2024.

This study looked at 351 patients who had been hospitalized with COVID-19 and compared them to 2,927 controls. Not surprisingly, there are small differences in brain structure that persist for over a year. A downside of this paper is potential p-hacking. An article in Scientific American reports the results are “equivalent to 20 years of aging.” I’ve glanced through the paper and I’m not sure how that claim was arrived at.

Brusaferri, Ludovica, et al. “Neuroimmune Activation and Increased Brain Aging in Chronic Pain Patients after the COVID-19 Pandemic Onset.” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, vol. 116, Feb. 2024, pp. 259–66.

This is an observational study so hard to draw inferences from. Depression and mental health issues are linked with brain inflammation although the direction of causality is debated.

Ellingjord-Dale, Merete, et al. “Prospective Memory Assessment before and after COVID-19.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 390, no. 9, Feb. 2024, pp. 863–65.

In this Correspondence Letter, the researchers report results from a cohort study on 188,137 Norwegians that ran between March 27, 2020 to April 26, 2023. Patients who have tested positive had somewhat worse memory scores and the effect persisted up to 18-36 months. There is an issue with this study, though, which is response bias.

(PREPRINT) Shan, Dan and Wang, Congxiyu and Crawford, Trevor and Holland, Carol. “Temporal Association between COVID-19 Infection and Subsequent New-Onset Dementia in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.”

Greene, Chris, et al. “Blood–Brain Barrier Disruption and Sustained Systemic Inflammation in Individuals with Long COVID-Associated Cognitive Impairment.” Nature Neuroscience, vol. 27, no. 3, Mar. 2024, pp. 421–32.

Partiot, Emma, et al. “Brain Exposure to SARS-CoV-2 Virions Perturbs Synaptic Homeostasis.” Nature Microbiology, Mar. 2024.

Safadieh, Ghida Hasan, et al. “Neuroimaging Findings in Children with COVID-19 Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Scientific Reports, vol. 14, no. 1, Feb. 2024, p. 4790.

Matthews, Beverly, et al. “Long-Term Cognitive Effects of COVID-19 Studied with Repeated Neuropsychological Testing.” BMJ Case Reports, vol. 17, no. 4, Apr. 2024, p. e256711

Hampshire, Adam, et al. “Cognition and Memory after Covid-19 in a Large Community Sample.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 390, no. 9, Feb. 2024, pp. 806–18

This is the key figure: A drop in Global Cognitive Score of -0.42 for those with Long COVID (>= 12 weeks duration) is equivalent to losing 6 IQ points.

Bonus appendix - a conservative Fermi estimate of expected days lost each year

First we have to estimate the average person’s chance of getting COVID-19 each year. Since people aren’t testing for or reporting COVID-19 very much, the current data is unreliable. However, recall that the wastewater data shows a similar amount of COVID-19 virus between 3/2023 - 3/2024 as between 3/2022 - 3/2023. The number of reported COVID-19 cases between 3/2022 - 3/2023 in the US was 72 million, or about 21% of the US population.

So suppose the chance of getting COVID-19 each year is 15% and it takes two weeks to recover. Then the expected loss of time each year is two days. If we factor in a 4% chance of losing a year to Long COVID then we have another expected loss of two days, or four days in total. If we factor in a 1% chance of losing 20 years then that adds 10 days, or a total of 14 days expected loss each year. Then we have to factor in the possibility of persistent brain damage as well as all of the secondary effects, such as spreading COVID to other people, lowered economic output etc. All of this adds up to a pretty compelling case for masking (with a well-fitting N95 mask or respirator.)

Acknowledgements - Thank you to Ben Ballweg and Cheryl Elton for helping proofread this.

I have been concerned by reports of excess deaths correlating with Covid vaccine administration. I haven't looked into it enough to evaluate the claims but they worry me. This is, after all, a new kind of vaccine without a long track record. (To anyone about to attack me here, I am a strong advocate of other vaccines.) However, your excellent piece is making me seriously consider getting a booster. Not sure it will do much despite my age of 60 since I recently had COVID for the first time and it was milder than a cold. But the long-term effects are disturbing, especially if they exceed post-viral syndrome for other viruses.

Great round-up of information, Dan. There are so many simple infrastructure-based engineering\architecture choices that could improve infection rates, like upgrading HEPA filtration options and airflow. If a DIY Corsi-Rosenthal box can make a statistical difference, it's just another symptom of pure denialism that basic steps aren't being taken. Declaring the "pandemic is over" is like declaring myself a millionaire; the numbers tell a different story than the assertion. The long-term implications are scary, but what's truly terrifying is the implications our mass-amnesia will have on the bird flu if it takes off in humans, with a 50% fatality rate. Posts like yours do make me feel less like chicken little screaming that the sky is falling. Data and evidence reign supreme, even if they're constantly evolving, and no matter what we would rather believe to be true.