A pro-science and pro-progress middle school health textbook from 1929

“This is a remarkable age. It is an age of skyscrapers, submarines, airplanes, dirigibles, phonographs, safety razors, radios, electric lights, steam and hot-water heat, gas stoves, vacuum cleaners, and other wonderful inventions. Many diseases have been conquered, and life has been lengthened. Life has been made more comfortable and in most ways safer. Such progress has been made that today the ordinary American workman enjoys more comforts and opportunities that were denied kings and queens a few centuries ago.”

So reads the end of page four of Science and the Way to Health, a textbook for middle schoolers written in 1929, long before Steven Pinker’s Enlightenment Now and the Progress Studies movement. The authors go on:

“Science is the wonder worker. What has brought about this remarkable change in the world? There is but one answer, — science. This is a word from the Latin, meaning ‘to know’…”

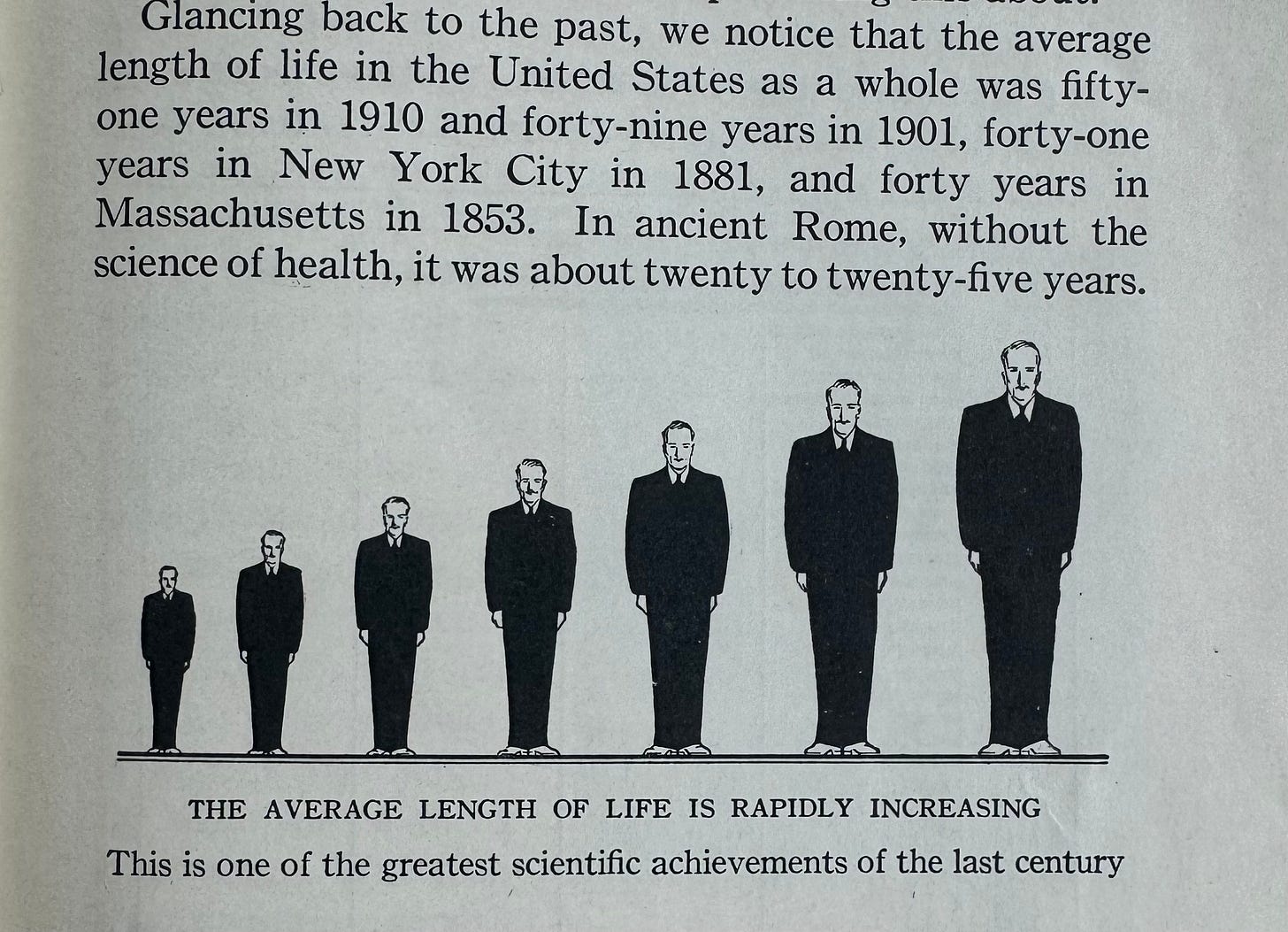

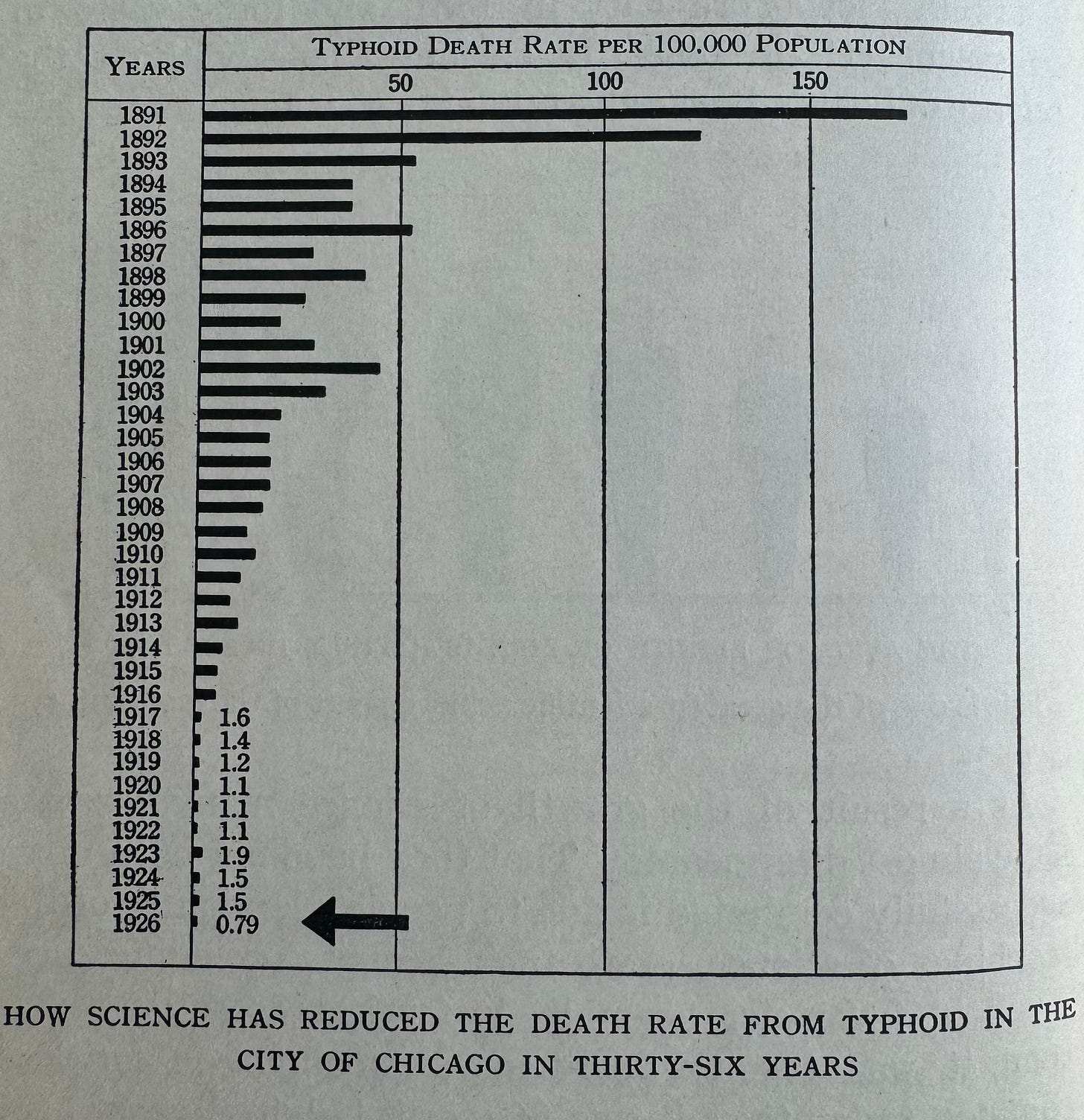

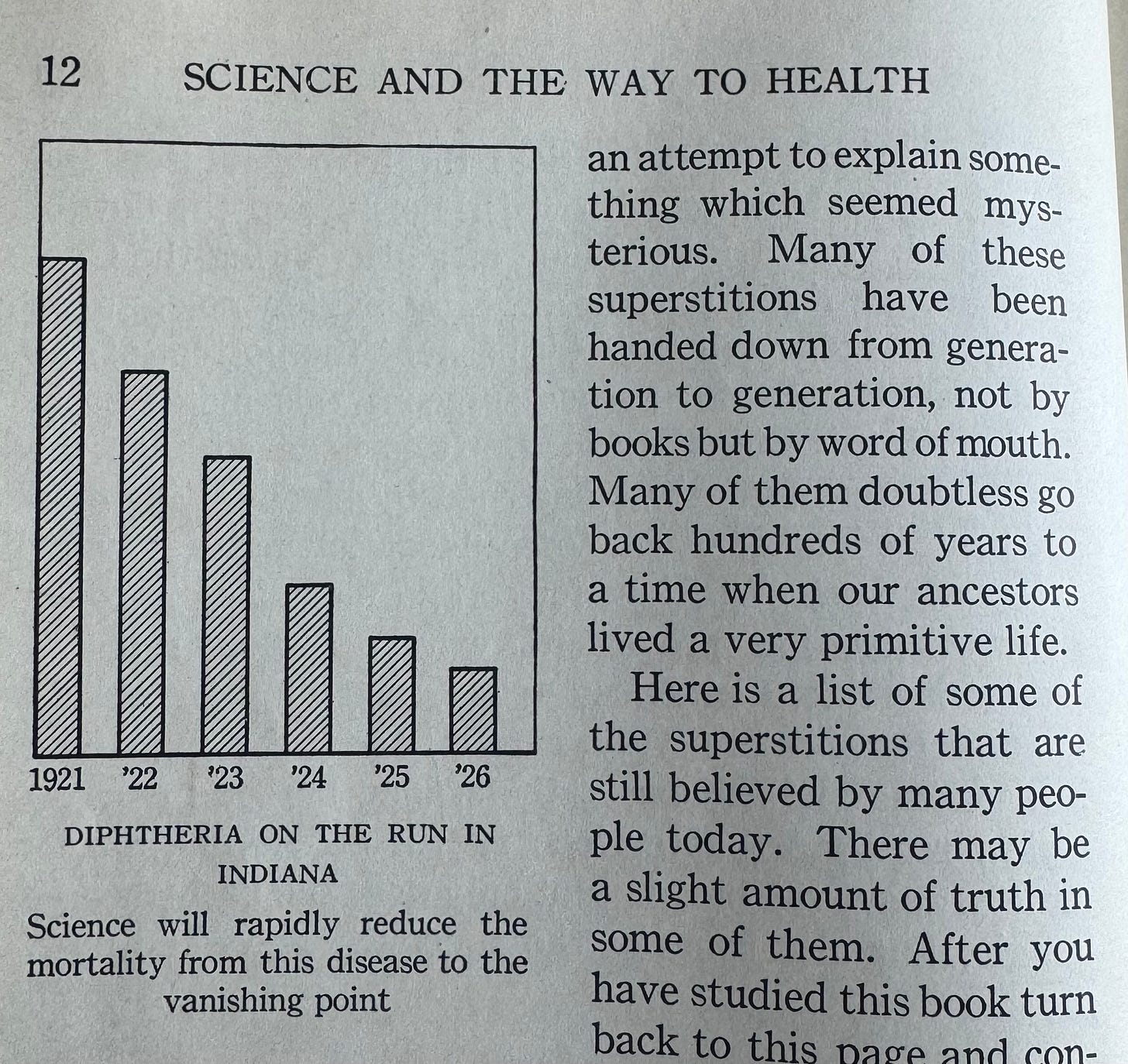

Two pages later, the book starts dropping graphs and discussions reminiscent of Our World in Data:

Remember typhoid from the game Oregon Trail?

Typhoid was largely eliminated in the United States due to insights from the germ theory of disease and better sanitation technology. In the 35 years between 1891 and 1926, the rate of typhoid deaths in Chicago dropped from ~170/100,000 to only ~1/100,000.

Scientifically advanced vs. scientifically primitive peoples

To show the power of science, the book contrasts modern man with scientifically primitive cultures that do not or did not have science. The book gives several examples of scientifically primitive people, along with data and anecdotes on how they are or were less healthy. The groups discussed are the native peoples of Panama, the Zulu, and Europeans in the Middle Ages. Wrong ideas are specifically described. For instance, the book discusses the Zulu’s belief in witch doctors, and also their belief that by inducing sneezes using “snuff” they can cure disease. With regards to primitive Europeans, the book discusses the medieval practice of bloodletting, noting that the practice is still sometimes still used as a “last resort” (in the 1920s).

Now, imagine the uproar that might ensue from some corners today if a textbook made this sort of direct comparison between two groups, with one group happening to be white and the other black. Some social justice warriors would no doubt raise an outcry. The book would be branded as Eurocentric, racist, and white supremacist, since it doesn’t give equal space to describing the intellectual achievements of the Zulu or to recognizing the validity of indigenous ways of knowing. The picture of the African witch doctor might be described as a “culturally insensitive caricature”. The book would also be criticized for not describing ways in which Zulu society is more healthy than contemporary American society.1

Yet, the book’s explanations are anti-racist.

The book posits that differential rates of progress are due to one group having access to and using ideas derived from the scientific method, which itself is an idea. The other groups, by contrast, ended up with ideas that were not scientifically derived and were in error. This explanation directly competes with any racist explanation that tries to explain differences as stemming from intrinsic biological differences (ie in intelligence or temperament). An assumption of biological difference may be natural for school children — after all, the Zulu look different on the outside due to genetics, so it is easy to imagine they may be different on the inside due to genetics. It also feels good to think that one is intrinsically superior. Of course, the full explanation for differential rates of progress around the world is much more complicated than merely what is described in the book, 2 but the role of the scientific method and the importance of good explanations (ideas) scarcely can be denied.

Valiant health knights

Chapter three is titled “Valiant Health Knights”. Here’s how it starts:

“Since the beginning of history illness and death have been a challenge to man. They have inspired his fear, resourcefulness, and courage.

At the beginning all was mysterious, but primitive man craved some explanation for sickness. Since science had not begun, he resorted to imagination and superstition.

…

Beginning with the seventeenth century there was light. Now enter the lists a long line of heroes who often lost their lives in the battle for humanity. The story of this conquest of disease — a conquest which is still going on — is one of the most fascinating stories of civilization.”

Over the course of 43 pages, the stories of the following “health knights” are told:

What stands out here is the praise lavished on these scientists. They are described as “heroes”, “knights”, and “martyrs”. Lister is described as “the prince of surgeons,” and it is said that “every modern hospital today is in a sense a monument to the intelligence and skill of Joseph Lister.” Words like “distinguished,” “beloved,” and “great” pepper the prose. Edward Jenner is called a “friend of mankind” who “made possible the conquest of smallpox.”

It is interesting how smallpox is described:

“In intelligent communities today smallpox is so rare that some physicians have never seen a case in their practice. About one hundred and fifty years ago it was so common that ten out of every hundred deaths were caused by smallpox. It was found in the hovel and in the palace… In the early eighteenth century it was unusual not to meet anybody on the streets of London whose face was not scarred by smallpox.”

America had a particular problem with anti-vaxxers then, just as it does today:

“Because of considerable opposition to vaccination, the United States unfortunately exceeds most of the civilized nations of the world in the annual number of smallpox cases.”

Heroic yellow fever “challenge trial” participants

The section on Walter Reed is quite interesting because it describes something like a challenge trial, with one of the two participants described as “one of the world’s great heroes.” In 1900, an epidemic of yellow fever broke out amongst the American troops stationed in Cuba. An army board led by Walter Reed was set up to figure out the cause of the disease. Reed suspected the mosquito was responsible. Two members of the commission allowed themselves to be bitten by mosquitoes while they were treating people with yellow fever. Both came down with the fever. This suggested, but did not prove, that the mosquito was to blame. To prove that the mosquito was the carrier, a quarantined area was set up and two “challenge trial” participants were recruited, a private named John R. Kissinger and another named Moran. These brave participants knew that they would likely have to suffer from the disease. Kissinger said “I volunteer solely for the cause of humanity and the interests of science.” His one condition for taking part in the experiment was that he was to receive no compensation. After living in the quarantined area for a period, both men were exposed to mosquitos that had fed on yellow fever patients. Both quickly came down with the fever. The rest, as they say, is history. The book describes how the eradication of mosquitoes from Panama made the construction of the Panama Canal possible and has allowed safe travel and trade to occur throughout the canal zone.

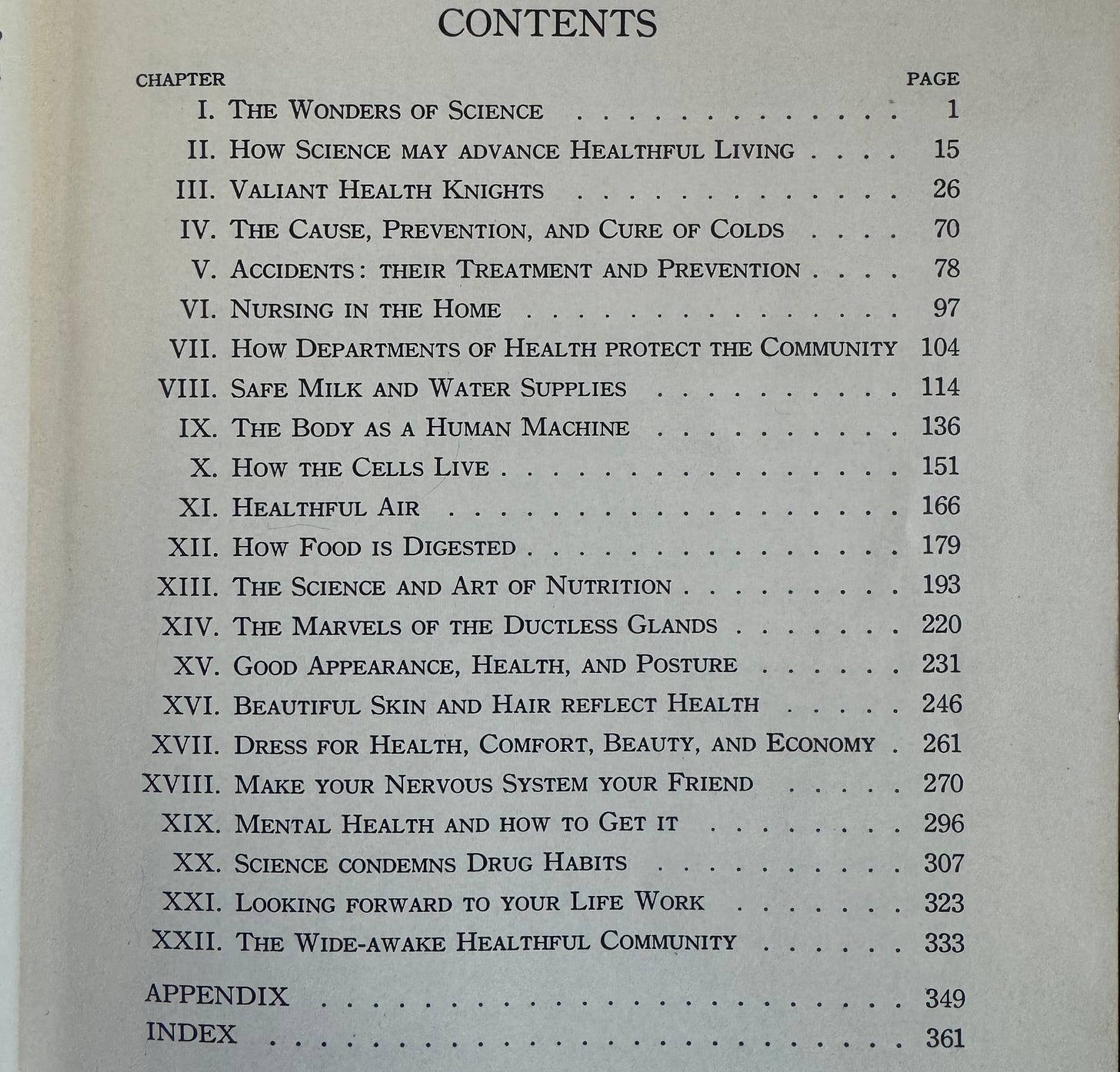

The rest of the book — pretty normal

The rest of the book is pretty much a normal health textbook, reflecting the state of scientific knowledge at the time. There are chapters on vaccination and public health, cellular biology, the human circulatory system, human skeletal and muscular anatomy, the human digestive system, nutrition, endocrinology, the human nervous system, mental health, and the dangers of alcohol and drugs. Notably absent is any discussion of the reproductive system or human reproduction.

Most of the information is still accurate, but there are some glaring and amusing anachronisms. For instance, the book says there are “about ninety” chemical elements, and it describes elevated body temperature during a cold as being due to “immune cells expending a lot of energy.”

There is a chapter on “dress for health, comfort, beauty, and economy” that posits that loose-fitting clothes are healthier than tight-fitting ones. It also says that high heels are bad for posture. (I have no idea if either of these are true but they both seem plausible.) Modern clothing designs, textiles, and fashions are described as superior to clothes from centuries ago, echoing a common theme of progress which permeates the book.

The book anticipates Slate Star Codex by 89 years by explicitly calling out the dangers of CO2 build-up in school rooms and bedrooms. The book recommends keeping windows cracked open:

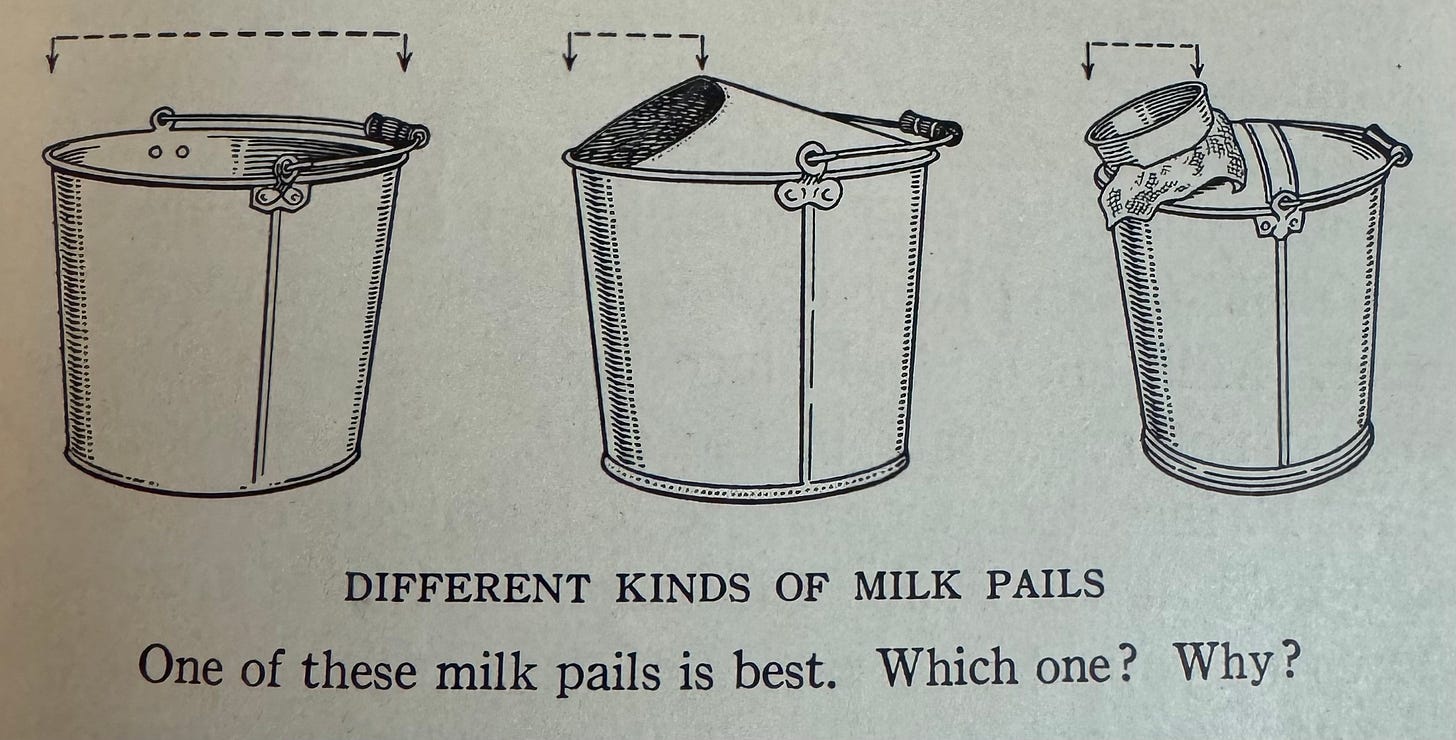

There is an entire chapter on “safe milk and water supplies,” things we take for granted today. The processes of pasteurization and water filtration are described in great detail and in glowing terms — at the time, such things were exciting “high tech” stuff! Techniques are described for designing wells to prevent contamination. The book goes into great detail about how to safely milk a cow, and how to safely store and transport milk. As an example of the level of detail, the book discusses the development of the milk can:

The book calls the milk can on the far right a “hooded milk pail.” The hood prevents dirt from falling off the body of the cow into the milk during milking.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the first three chapters of this book are truly remarkable. The first chapter acknowledges progress as real and desirable. The authors present graphs and data to prove that human health is getting better. The book explains how progress has been unlocked by the scientific method, and it contrasts the health of groups of people who have science with those who don’t.

The second chapter is entitled “How Science May Advance Healthful Living”. It is all about how science can inform how we should live our lives, and gives many examples of daily practices for healthy living.

Chapter three highlights many heroes of science, providing role models for school children. They are framed as “valiant health knights.” They are described as “courageous” several times, which is interesting because the virtue of courage is hardly ever mentioned today.

Some of the later chapters are examples of what Jason Crawford calls “industrial literacy,” since they explain all of the remarkable advancements and technologies that undergird things that might otherwise be taken for granted. In particular, the chapter on “safe milk and water supplies” stood out in this respect. To a lesser extent, the chapter on “healthful air” and how modern buildings are ventilated also fits the mold.

It would be interesting to contrast this textbook with middle school health textbooks today, to the extent that health is still taught at all in middle school. I recall taking two health classes in middle school, but I don’t remember anything remotely like what is in this book being taught.

To be clear, these sort of “ultra woke” views come from a vocal fringe. If you think the attitudes I am describing sound like an unrealistic caricature of what some people believe, read the book “Galileo’s Middle Finger” by Alice Dreger.

Africa’s geography, for instance, is not conducive to trade, which hindered economic development and the exchange of ideas over long distances. Jungles and harsh terrain made the growth of agriculture difficult, and the tropical climate led to a higher disease burden, which lowered life expectancy and made the development of population-dense cities difficult. ChatGPT informs me that “Trypanosomiasis, spread by the tsetse fly, specifically limited the use of draft animals, such as oxen and horses, for agriculture and transportation in large parts of sub-Saharan Africa.” Later, European colonialism contributed to keeping the Zulu and other African peoples in a state of poverty and relative ignorance longer than would otherwise have happened.

Hi, great post. I added it to HackerNews and it is getting very interesting comments. https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=42317952

When it talks about 'tight-fitting clothing' it probably isn't referring to what you would mean if you talked about 'tight-fitting' clothing in normal conversation today, it's referring to things like corset training, which is clearly bad for you. Normal tight fitting clothes are fine. High heels are terrible for your feet and legs during the duration you're wearing them and if you wear them a lot can cause your triceps to be tight which is bad for your posture. So not the best way of describing what's bad about high heels but not completely false either, sort of in the neighborhood.