German scientific paternalism and the golden age of German science

1880 - 1930

John Ziman (1925 – 2005) was a condensed matter physicist who spent most of his life working in England.1 In addition to being a first-rate physicist, he was also a humanist and early metascientist.

As part of the research I did for my article on peer review, I read some of a book by Ziman called Public Knowledge: The Social Dimension of Science, which was published in 1968. The book is notable for containing a strong defense of peer review. So far I’ve read about half of it, and one of the most interesting parts has been his description of German science prior to Word War II. That’s what I want to dive into here, but first, let me give some context on the book:

Background on Public Knowledge: The Social Dimension of Science

In the first chapter of the book, Ziman considers several approaches towards defining what science is that have been proposed by philosophers. Ziman points out that philosophers thus far have generally framed science in terms of an abstract method. If someone is following that method, they are doing science.

The central thesis of Ziman’s book is that science is not a solitary activity. This is because the end goal of science is not just knowledge but public knowledge. Public knowledge consists of truths that have been agreed upon through a process of consensus building among many scientists.

Thus, a person stranded on a desert island cannot do science:

“Technology, Art, and Religion are perhaps possible for Robinson Crusoe, but Law and Science are not.” - pg 10

A scientist’s allegiance should be toward the creation of a consensus:

“What I have tried to show, in Chapter 3, is that the criteria of proof in Science are public, and not private; that the allegiance of the scientist is towards the creation of a consensus.” - pg 78

For Ziman, a full account of what science is must include methodological, psychological, and sociological elements. Ziman’s thinking was highly influenced by his contemporary Robert K. Merton, one of the founders of the field of sociology of science. Indeed, he cites several times Merton’s 1942 paper on “scientific norms”.

Ziman describes the peer reviewer as a “linchpin” in the process of consensus building. This is in part because peer reviewers help ensure that scientific arguments conform to high standards of rigor and objectivity, rather than drifting into sloppy reasoning and polemics. For Ziman, the scientific literature is an important resource which must be protected. It is also the stage where debates play out, and peer reviewers (“referees”) help make sure those debates play out in a civil way. Ultimately, the consensus is what appears in textbooks and is taught in university classrooms.

I say all this just to provide an overview of what this book is about. What I wish to focus on in this post is Ziman’s description of German science prior to World War II, which appears in Chapter Five.

German scientific paternalism

Chapter Five is entitled “The Individual Scientist,” but it’s really about the processes by which scientists are created.

In the very old days, scientists were oddballs, willing to withdraw themselves from normal society. Many found themselves in tension with existing orthodoxies and establishments. They were supported by their own funds or wealthy patrons. This system limited the number of scientists in the world. Even if there had been lots of patrons willing to fund science, people are not naturally prone to becoming scientists. Becoming a good scientist requires walking a “straight and narrow path”. In the old days, some managed to walk that path, but many brilliant individuals fell off into quackery, religion, or the occult instead.2

The development of academic institutions for scientific education and research greatly expanded the number of scientists in the world. Now people could be trained to walk the scientific path. The new institutions captured people who would have otherwise gone into other fields like law or business. They were then trained in the methods and norms of science and provided jobs in scientific research.

According to Ziman, these institutions first arose in Germany. Here’s the key passage (trimmed down):

“The German universities, which seem to have been the first large-scale, self-consciously professional research organizations to offer a career of Science and Scholarship to anyone with the talents for it, depended upon a system of deliberate apprenticeship. This system, being in fact a State Civil Service, was very formal and rigidly hierarchical…

… During his long apprenticeship, the German academic internalized the conventions and criteria of the scientific life. From bitter experience he learnt not to get caught in personal controversy, nor to speculate on the basis of inadequate evidence. Under the harsh eye of his own professor he acquired the habit of checking and re-checking his observations, of writing accurately and impersonally, and of being the foremost critic of his own work. The carrot of a juicy Chair drew forth his utmost of energy and imagination — yet always within the constraints of the discipline of his seniors.

In its day, the German academic system was the admiration of the world, and extraordinarily successful as a medium in which scientific research flourished …

… There was a price to pay. The individual scientist was no longer working solely for his own amusement, nor for the abstract advancement of learning, or for posthumous glory; he was also seeking personal promotion. As we are now fully aware, this is the catalyst for the release of vast floods of tedious, prolix minutiae, impressive for quantity if seldom for quality; 'publish or perish' is not a new cry…

The mechanisms of character formation which drove the German academic system were paternalistic-often patriarchal. The power of the Professor Ordinarius3 over his students and assistants was almost that of a Roman father over his family. Upon his recommendation depended all hope of promotion …

… The German system emphasized the social character of the Wissenschaft by making sure that every new discovery or theory was thoroughly examined and exhaustively tested before admission into the consensus. The virtues that it most strongly encouraged were those of painstaking care, loving attention to detail, precision of language and argument. No side turning was to be left unexplored, no gaps were to be tolerated in the logic. The great era of German Science (which died in 1930 and has not been revived) was not only an age of experimental, observational and textual discoveries; it was the age when the foundations of Pure Mathematics were drilled deeper, to reach the firmer bedrock of formal logic; it was an age of the treatise and Handbuch, and of scientific and technological education.

It is the argument of this essay that such attention to observational accuracy, logical rigour and encyclopedic detail is quite as essential to Science as imagination and inspiration. Without these 'Germanic' virtues, Science would disintegrate into schools and sects, prophets and their coteries of disciples.

But the enforcement of high critical standards by distant, anonymous authorities and institutions, such as those of editors, referees and review writers, is psychologically impracticable. The public peace is not preserved by the abstract power of the impersonal judge and vigilant policemen; it depends in detail upon the conscience of the individual citizen, moulded in childhood by the direct and personal influence of stern but loving parents. High critical standards must become part of the intellectual conscience of the scholar; he must acquire the psychological strength to withstand the temptation of shoddy thinking and tawdry brilliance. The paternalistic upbringing of the German academic of the old school gave him this moral stiffening in its most puritan mood.”

Ziman goes on to contrast the German system with the systems that evolved in the UK and America. I’ve scanned and uploaded the entire chapter to my website, if anyone wishes to read it.

The historical record

The historical record somewhat supports the notion of a “golden era of German science” spanning the fifty year period between 1880 and 1930. During this period the German language was dominant in many fields of science. As late as the 1960s many important scientific texts could still only be found in German.

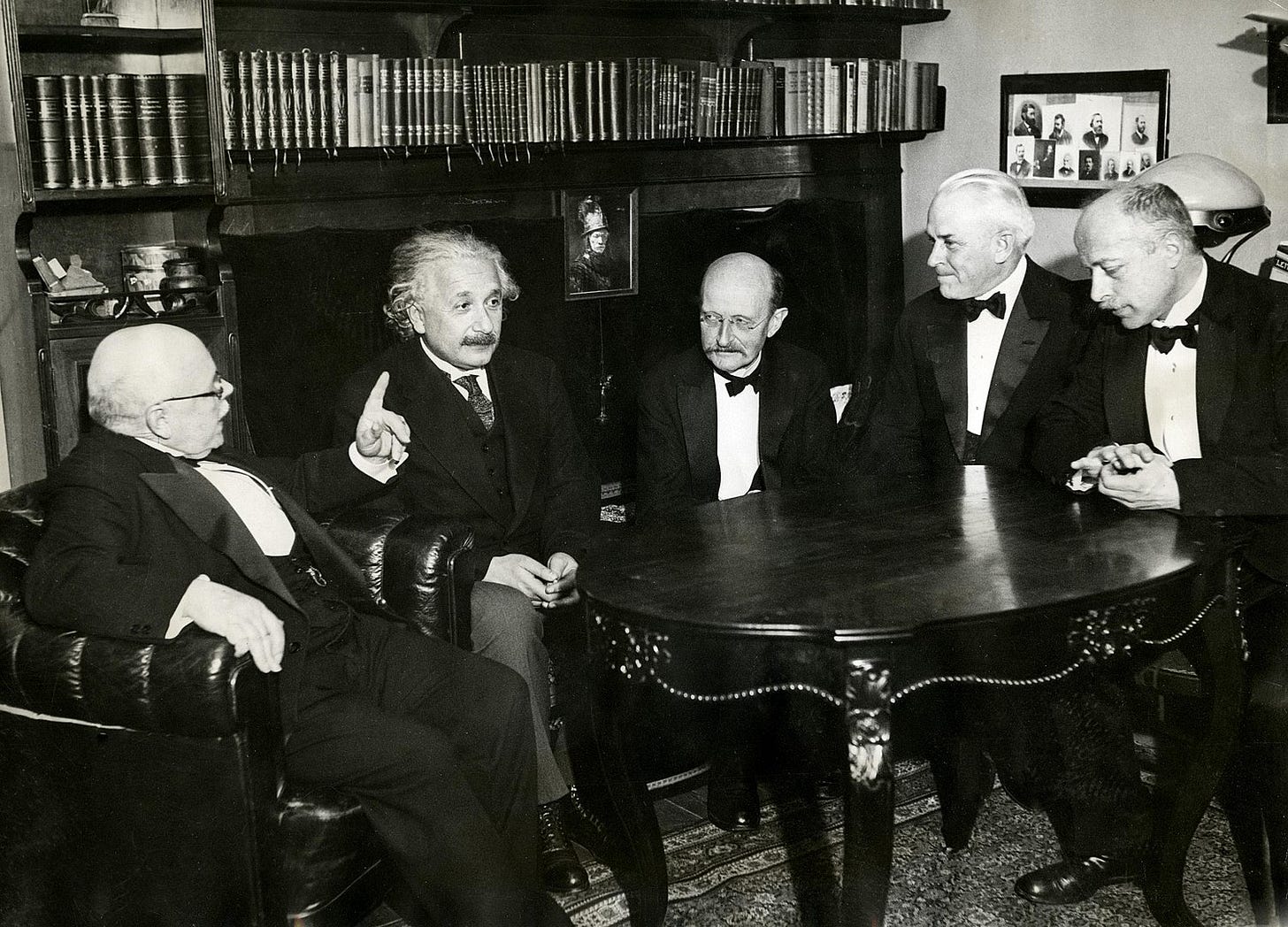

The foundations of quantum mechanics (“Quantenmechaniks”) were chiefly developed in Germany during that period, as well as in nearby Copenhagan. The quantum revolution got kicked off with Max Planck’s quantization of electromagnetic waves in 1900. No single individual invented the theory of quantum mechanics — it was the result of an intense period of collaboration between many theorists and experimentalists. Some Germans who were involved in this were Max Planck (1858–1947), James Franck (1882 - 1964), Gustav Ludwig Hertz (1887–1975), Werner Heisenberg (1901–1976), Max Born (1882–1970), Wolfgang Pauli (1900–1958), Pascual Jordan (1902–1980), Arnold Sommerfeld (1868–1951), Otto Stern (1888–1969), and Albert Einstein (1879 - 1955).

Moving beyond quantum mechanics, Wilhelm Röntgen (1845–1923) discovered X-rays in 1895. X-ray crystallography was invented by Max von Laue in 1912 and further pioneered by Paul Peter Ewald (1888–1985). Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner did pioneering work together on radioactivity between 1907 and 1938. In chemistry, Haber and Bosch invented the process for creating ammonia in 1909. Walther Nernst (1864–1941) pushed forward the theory of thermodynamics, developing the third law of thermodynamics between 1906 and 1912.

There were other important scientists who came from elsewhere to work at German universities, such as Erwin Schrödinger, who was Austrian but did all of his work at German universities. Felix Bloch (1905 – 1983) did his Ph.D. under Heisenberg, as did German-born Rudolf Peierls and many others. Many of the most famous Hungarian “Martians” from that period went to Germany to study or work there. John von Neumann (1903 - 1957) studied under David Hilbert at the University of Göttingen and later worked at the University of Berlin. Hungarian Theodor von Kármán (1881–1963) was director of the Aeronautical Institute at Aachen University in Germany between 1908 - 1930, where he made seminal contributions to aerodynamics. Hungarian polymath Michael Polanyi (1891–1976) worked at the University of Karlsruhe and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin. The Hungarians Edward Teller (1908–2003), Leó Szilárd (1898–1964), and Eugene Wigner (1902–1995) all worked for many years in Germany until they were forced to emigrate to America during the Nazi’s great purge of 1933 (all of them came in helpful during the Manhattan Project).

In biology, Robert Koch (1843–1910) did pioneering work on bacteriology, discovering the bacteria for tuberculosis, cholera, anthrax, and other diseases. Max Weber (1864–1920) made contributions to sociology. In psychology, the Germans Max Wertheimer (1880 – 1943), Kurt Koffka (1886 – 1941), and Wolfgang Köhler (1887 – 1967) invented the field of gestalt psychology and pioneered the science of perception. In geology, Alfred Wegener (1880-1930) came up with the continental drift theory. Mathematical advances were made by David Hilbert (1862 - 1943), Edumund Landau (1877 - 1938), Georg Cantor (1845 – 1918), Felix Klein (1849–1925), Hermann Minkowski (1864–1909) (who was also Polish/Russian), Emmy Noether (1882–1935), Erhard Schmidt (1876–1959), Hermann Weyl (1885–1955), and others.

Delicate balancing acts

Creating social institutions that consistently produce high quality science is very challenging, involving many delicate balancing acts:

Maintaining high standards without choking science with bureaucracy

The rigid hierarchy of the German academic system allowed those at the top to enforce very high standards of rigor. As just outlined, the historical record shows this system worked well. There were downsides, however. Some scientists became overly focused on climbing to the next level in the hierarchy, resorting to whatever means they could use to do so. Often this boiled down to publishing incremental or highly derivative work at a high rate to impress superiors. Such work may have been rigorous, but it was also boring, resulting in little advancement for science. More generally, these sort of systems can be prone to bureaucratic sluggishness — people end up spending too much time “checking with higher-ups” and ensuring compliance with rules. Rigidly hierarchical systems can also be slower to change, since the people at the top often resist change. People at the top are usually older and often have the most to lose from any dramatic advances. In his book, Ziman talks about how the less-hierarchical American academic system in the 1960s was faster at absorbing and teaching new ideas, relative to the systems in the UK and Germany. However, Ziman claims that the nimbleness of the American universities was not without cost. He says that American researchers would more easily get caught up in passing fads and fashions, and that this came at the expense of their mastery of more timeless fundamentals. According to Ziman, American Ph.D.s also were lacking in “critical attitude,” although they tended to be more proficient with the latest techniques.

Teaching respect for the consensus without slipping into dogmatism

The current consensus demands respect, especially in more developed fields like physics. At the same time, the scientist must be trained to remain open to change, even revolutionary change. Achieving the right balance here is not easy. Most science takes place within the confines of existing consensus knowledge and some overarching theoretical paradigm. Even during periods of revolution, existing consensus knowledge must be explained by the new paradigm. So, understanding the existing consensus is important, as is refining the ways in which the knowledge in the existing consensus is ordered and formalized. Furthermore, most scientific advances take place within a paradigm — this is what Kuhn called “normal” science. If too many people work on trying to develop a new paradigm, this would come at great expense to “normal science.” At the same time, the current paradigm and existing consensus should not be revered as an orthodoxy that is beyond questioning.

Regulating scientific communication without squashing bold new ideas and eccentricity

Ziman is adamant that scientific communication should take place within the regulated confines of peer-reviewed journals. He views the integrity of the scientific literature as sacrosanct. In his view, each peer reviewer (referee) acts “like a traffic policeman on point duty, keeping the traffic moving smoothly by imposing an orderly succession and conformity to the general rules.” One important function of referees and editors, Ziman notes, is to enforce standards of communication, something I talk about in my article on peer review. Of course, the potential downsides to gate-keeping by peer reviewers and editors have been much discussed — bold new ideas may have a harder time getting published. Ziman acknowledges and discusses this trade-off.

Establishing science as a career for the masses, without it becoming just a career

Ziman discusses the “mass production” of scientists that kicked off after World War II. He talks about how the “American graduate school” had replaced the “German Institut.” Relative to European schools, the American schools had larger class sizes, more coursework, and more focus on exams. He sees both pros and cons to this. According to Ziman:

“The strength of the old German system was the way in which the spirit of enquiry was passed on as an oral tradition.”

According to Ziman, it is harder to pass on this “spirit” through “mass methods.” Students become focused on getting good grades and impressing their professors. When they start research, their focus is on publishing papers and getting citations. They hope to achieve a “breakthrough” to garner plaudits from those around them and broader fame from society at large. When the focus is on such parochial things, the deeper and broader picture of what science is about can be lost:

“He does not see himself as engaged in a larger struggle with ignorance and error, as a member of a great movement, as a contributor to man’s understanding of nature. The graduate school, by its mechanization of learning, has thrown philosophy out of the window.”

Conclusion

Even if one is able to create a scientific system that balances all of these things correctly, it is yet another thing to keep it going — the processes and norms of the system must be faithfully inculcated into each new generation. The cataclysmic disruptions caused by the Nazis quickly drew the curtains on the golden age of German science. Rebuilding German science to where it is today took decades to achieve.

(Not to be confused with Pieter Zeeman, for which the Zeeman effect is named)

Others, like Newton, zipped and zoomed between science and the occult. Ziman breaks the history of science into two phases. The first was the era of largely self-taught and highly independent scientists, often fighting against entrenched orthodoxies. The second phase was that of career scientists, whose development was moulded by systems for scientific education. Scientists from the first era play a prominent role in our histories, and their personalities and iconoclastic behaviors are often idolized. However, Ziman thinks the second era was a definite advance over the first. Here’s how he describes things: “The virtues of curiosity, intellectual freedom, and questioning of all accepted doctrines, etc., which were so essential in that phase (and which are, of course, still essential to good science now), are not sufficient to make a man into a successful research worker. Those virtues are to be found in many cranky, eccentric persons, whose would-be contributions to Science are worthless because they have not been subjected to the consensible discipline. In our histories of Science we celebrate the successes of that small band of warriors whom hindsight informs us to have been on the right track; we do not bother with all the other little bands, wandering in the wilderness with strange philosophical and religious banners…”

As Ziman explains, departments at German universities during that period often revolved around one or maybe two star faculty that everyone was working under. Today, this sort of system is frowned upon. The scientists at the top had the title Professor ordinarius, and they held a Lehrstuhl or "academic chair.” The rank below that was that of Professor extraordinarius, followed by Professor. Below that were academics who primarily engaged in teaching who had achieved the rank of privatdozenten (an equivalent in contemporary America would be an Associate Professor who primarily engages in teaching).

Excellent review 🎯💯✅ & very nice explanation of the success of German scientific system in its Golden Age. I would argue that there’s private science & public science; I also would also argue that falsifiability is important. I think we need to be careful about enshrining the terms science scientists and scientific… I’m ok with people with great intuition. I think rigor & public/ peer scrutiny are vital if one is looking for official accolades & public funding… it’s still ok to do experiments & try out theories & note them in private journals just for fun 😎. Thank you for another really great article