Why AI doctors should not be FDA regulated

The FDA is a sacred cow in medicine. Thus, it was refreshing when I saw a recent critique of the FDA’s current system for AI regulation published in PLOS: Digital Health.1 The authors include medical researchers from the Harvard T. H Chan School of Public Health, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. They are a bit shy about how they state it, but their proposal is rather radical — they call for a major curtailment of the FDA’s role in AI regulation and a shift towards decentralized systems for AI oversight.

The authors argue their position on grounds of practicality and their belief that decentralized systems of regulation will work better. Furthermore they believe decentralized systems will be required regardless of what happens at the FDA. I have recently started to come around to a similar view, but following somewhat different lines of argument. This article is an attempt to synthesize those different strands of argument.

The current system is going to break down soon

The number of AI approvals that the FDA has been processing has been growing exponentially:

While the FDA can hire contractors, the number of federal jobs at the FDA is largely fixed baring an act of Congress. It appears likely that soon the FDA will not be able to keep up with the number of applications they are receiving, which will slow down approvals and put a damper on medical AI innovation.

Unlike drugs and vaccines, which are mostly over-regulated, and medical devices, which are arguably a bit under-regulated, I think thus far the FDA has struck a relatively good balance in how they regulate AI.2 If anything, their requirements have not been strict enough. Most notably, as many have pointed out, the FDA does little to check for racial or gender bias in AI systems.3

Still, the costs and complexity of getting an AI system through the FDA are nothing to sneeze at. It currently costs at least a million dollars and about a year of work to get FDA approval for a narrow single-use AI system (assuming you remain in good standing with the FDA and don’t get capriciously screwed over like MELA Sciences was).

The current regulatory burden is already dampening innovation. It appears to me that many useful AI systems developed in academia are not being commercialized or used in clinical practice due to the cost and complexity of getting them through the FDA.4 An analysis of FDA submissions by Rock Health shows that between 2019-2022 an increasing fraction of submissions started coming from large tech companies rather than startups. This is a worrying trend.

The costs of getting through the FDA are only expected to increase as we move from narrow single-purpose systems towards more general systems that will be intended for many different uses. As we discuss in the next section, there may also be an extended wait period while companies wait for the FDA to develop procedures for more general AI systems.

The FDA has no idea how to regulate general purpose AI

It’s now clear that foundation models like GPT-4 are the future for medical AI. In a recent study, medical professionals rated responses by ChatGPT vs doctors on Reddit and generally favored ChatGPT’s responses. Another study from Massachusetts General Hospital concluded that ChatGPT and GPT-4 can both be useful for guiding radiological decision making in the context of breast cancer screening. Google recently unveiled “Med-PaLM-2”, a model which achieved a score of 85.4% on the US Medical Licensing Exam. Google is now working on a multimodal version that can analyze both a patient’s EHR records and medical images. Microsoft and Oracle are also developing multi-modal foundation models for medicine.

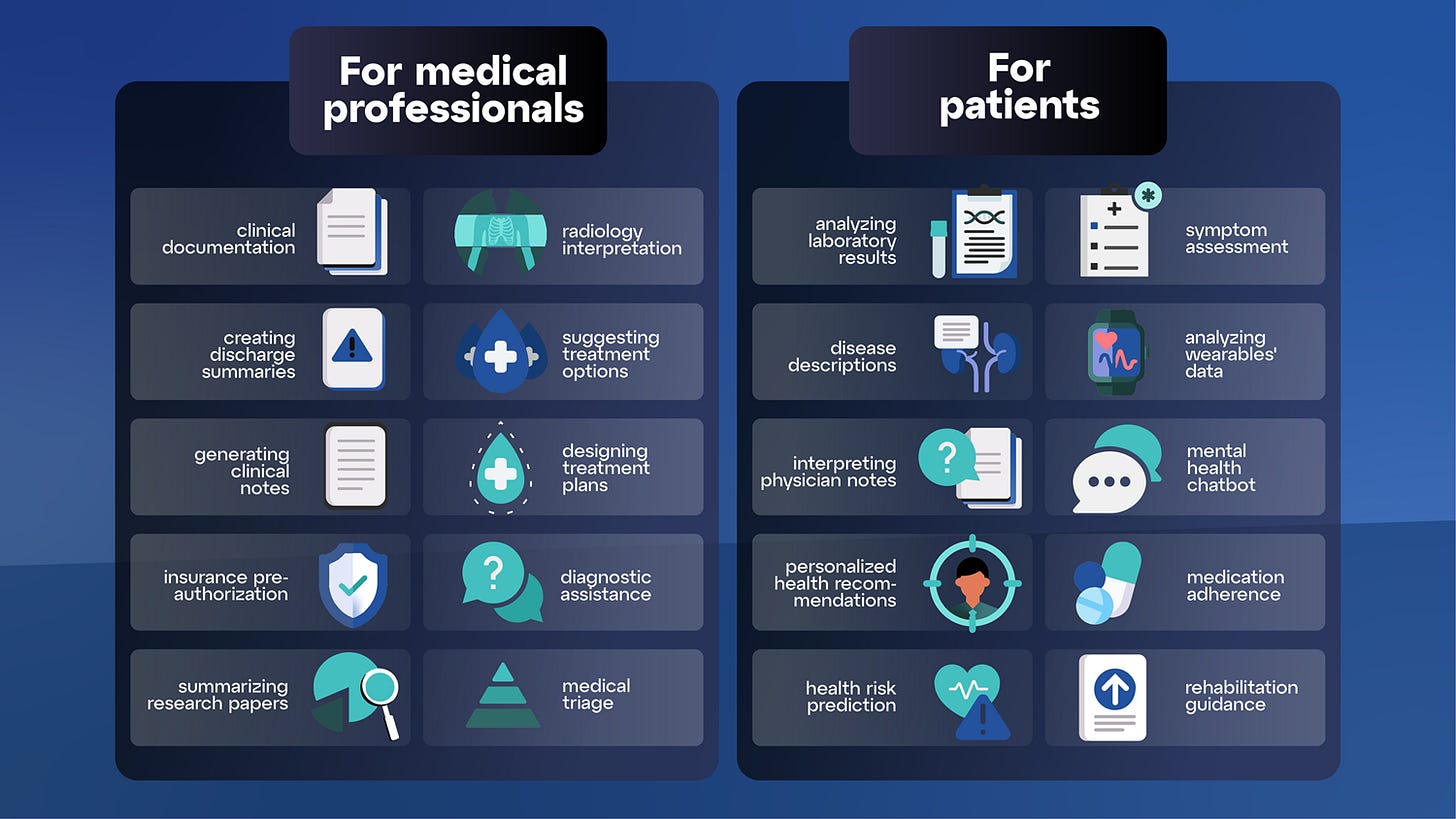

In April 2023 a service called Dr. Gupta AI was unveiled which uses a GPT-4 like model to simulate a doctor. The company issues a lengthy disclaimer that the system should not actually be used for diagnosing and treating any disease (which I’m guessing many people will ignore). A company called Hippocratic AI recently raised $50 million to develop an LLM for healthcare that will help doctors with “non diagnostic tasks”. A Kickstarter campaign is raising money for “Galen”, a medical AI chatbot that will “provide answers and explanations about complex medical topics”.

The FDA has no idea how to regulate general-purpose medical AI systems like these. At a recent event I went to at MIT, a person from the FDA was asked how they are planning to regulate AI chatbots. They just threw their hands up and said they had no idea. One wonders how long AI companies will have to wait for answers — the FDA does not have a track record of moving very fast in response to new technologies.

Even if the FDA were to invent schemes for regulating general purpose medical AI, there will likely be ways around them. First, it’s sometimes possible for companies to sneak around the FDA by making very few claims about what their AI can be used for and issuing very lengthy disclaimers. I have seen a couple startups trying to do this (but I’m not sure how successful they will be long term).

There is also a new paradigm for developing medical AI that presents a way hospitals can avoid the FDA. It’s called “foundation models as a service”. The service allows hospitals to connect their EHR, imaging, and radiology report databases to a cloud-based service where a foundation model will be trained or fine-tuned on all the hospital’s data. If the data is carefully stripped of personal health information then burdensome HIPAA requirements might be avoided. If the hospital only uses the resulting AI system internally and isn’t selling it, then the general thinking today is that FDA approval is not required.5 Still, this is a grey area legally - FDA lawyers might be able to argue that in effect the hospital is buying an AI from the company providing the service.

You have a First Amendment right to listen to an AI, regardless of what the FDA says

The first amendment guarantees everyone the right to publish information but equally importantly it guarantees everyone the right to access whatever information others are willing to provide. When you ask an AI for medical advice you are retrieving information from it that was put there by the manufacturer during training (as well as any data the AI is holding in its context window).

Suppose you have a mysterious illness. You have the right to ask literally any person to investigate your case and render advice. You also have the right to buy any book to get advice. You can also ask Google or consult a smartphone based symptom assessment app like Ada. Or you may consult medical references like UpToDate which often contain complex algorithms (like flowcharts) that assist in making a diagnosis. FDA approval isn’t required for any of those things. So why is FDA approval required to get medical advice from an AI? Well, because the FDA says so.

Somewhat unfortunately the legal definition of a “medical device” is so broad that essentially anything used in medicine might be considered a medical device if the FDA deems it so. This includes health-related books, apps, and educational materials. The only reason such things aren’t regulated by the FDA is the FDA has issued statements deeming them as excluded. In the past the FDA has regulated urine and saliva specimen containers, toothbrush containers, and mattresses with speakers as medical devices. (As another example, the FDA regulates lab-developed tests as medical devices even if they are just being used internally and aren’t being sold.)

In lieu of the legal definition of a medical device becoming more focused, the first Amendment can provide a bulwark against FDA overreach. An example is the battle between 23andMe and the FDA. In 2013 the FDA issued a “cease and desist” letter to 23andMe telling them they were not allowed to take risk information from peer reviewed literature and their own data analysis and provide it to customers. The FDA was worried about hypothetical scenarios where consumers would overreact to the information provided. For instance, they were concerned that women who learned they were at higher risk for breast cancer might rush out to have their breasts removed without properly consulting with their doctor or learning the risks involved in the procedure. On the basis of the notorious precautionary principle they sought to ban all reporting of risk information to consumers because of a possible harm that had little theoretical or empirical basis in reality, while ignoring the risks of not allowing information to flow freely. In reality multiple studies dating back to 2009 show that people who receive genetic risk information are actually quite rational and do not take such drastic actions.6 After mass outcry, much of which was based on First Amendment arguments, the FDA eventually relented in 2015.

As another example, the FDA once prevented the company Amarin Pharma Inc. from sharing information with consumers about a clinical trial it had run (ironically, the trial had been approved by the FDA and was successful). The company sued the FDA and won. As Alex Tabarrok has written about, the FDA has lost many such lawsuits with courts regularly siding with the First Amendment over the FDA.

At an AI for health conference I asked prominent Harvard legal scholar Glenn Cohen about these issues. He was skeptical that the First Amendment would have teeth against the FDA. He pointed out that the FDA already has significant ability to limit speech, for instance by restricting the claims that companies can put on labels for supplements and drugs. Also, all food has to be accurately labeled. Such things are well and good. However, I’m pretty convinced there is a pretty strong legal case here when it comes to AI. Other legal scholars agree. In a 2015 article legal scholar Adam Candeub argues that no software for digital medicine should ever be classified as a FDA-regulated medical device due to First Amendment protections.

Advanced AIs constitute a new form of medical practice

“The practice of medicine is not currently regulated in the same way as drugs or medical devices are, yet the current approach to regulation of clinical AI implies that when codified in machine learning algorithms it should be.” - Panch et al., page 5.

The FDA is not allowed to regulate practice of medicine. To the degree medicine is regulated, it is done so on the state level. The FDA can’t shut down homeopathy, crystal healing, acupuncture, cupping, energy healing, and other worthless practices which make false claims and bilk people out of their savings, harming them in the process.7 There are good reasons for this. Medicine is extremely complex, nuanced, and contextual. For the most part, decisions about medical care should be made locally between a doctor and their patient, rather than trying to have a far away agency dictate what can and can’t be done. After all, your personal physician has most information about the specific details of the your own case. We have other systems for maintaining a high quality of medical care in such as medical licenses and tort law. Additionally, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and insurance companies work hard to make sure patients get the best care at the lowest cost by dictating what sorts of tests and procedures will and will not be covered. Hospitals also have a financial incentive to provide the best care, lest their reputations suffer and patients go elsewhere. Most major hospitals hold regular private “morbidity and mortality” meetings to surface mistakes that were made and make improvements. In some cases doctors (often older senile ones) who are making a lot of mistakes are asked to retire. Finally, patient advocacy groups lobby for changes to be made at hospitals and insurance companies.

The gap between what a doctor does and what AIs can do is getting narrower every day. It’s clear that the usage of advanced AIs will constitute a new form of medical practice. We need to move away from viewing AI systems as FDA regulated medical devices and treat them like “digital doctors” instead. If we don’t think that the FDA should regulate doctors, then why do we think it should regulate AI doctors? All of the ways we do oversight on doctors should be ported over to advanced AIs. This transition will not be easy, but it needs to be done.

Conclusion: premarket FDA approval should not be required for most AIs

“.. centralized regulation alone will not be able to address the reasons that algorithms might fail or increase disparities due to local context and practice patterns, thereby inevitably eroding trust.” Panch et al., page 5.

In the paper referenced at the start of this post Panch et al. give a bunch of arguments against continuing with the current system for medical AI regulation. The first thing they discuss is how a growing number of submissions is starting to strain the system. They then talk about the growing need for AI systems to be regularly updated as data sources change and medical knowledge advances.8

Next they discuss a bunch of issues with current AI systems, such as bias and the inability to distinguish correlation from causation. These points just underscore the need for some sort of oversight. Many reflexively point to the FDA as the answer. Yet we must consider the possible downsides of such an approach and consider other solutions.

The current FDA system assumes that each AI system will be designed and used for one narrow purpose. Yet this is not the case even today. In practice systems marketed for triage may be used for diagnosis, and diagnosis systems may be used for triage. As with drugs, the FDA cannot control how AI is used locally, they only set the indication on the “label” and the claims the company is able to make. As AI systems become more general and capable they will be used in more and more unexpected ways. Thus, even if the FDA AI regulation continues, there will be a strong need for local oversight. Right now, however, everyone is looking to the FDA rather than considering other approaches. This is a mistake which will ultimately lead to an erosion of trust in AI. Here’s how the authors put it:

“A specific AI technology or device, regulated in isolation, cannot account for local socio-technical factors that ultimately determine the outcomes generated by technology in healthcare”. Panch et al., page 2.

Panch et al. argue that in the future oversight will be best achieved through each hospital having a “department of clinical AI” that understands local needs, data streams, and usage patterns. Such a department would be in charge of monitoring all the AI systems that are deployed and keeping track of how they are being used. Perhaps such departments will even retrain their AIs periodically to adapt to changes in medicine, similar to how doctors receive continuing medical education.

Panch et al. also foresee tort law playing a role as well. The details still need to be worked out but the basic idea is that just as a doctor can be sued if they deviate from standard of care, hospitals may be sued if their AI systems are not following standard of care. Notably this is different from the current thinking that the manufacturer of the AI should be held liable rather than the doctor or institution using the AI.

Oversight on AI can and will be achieved via many other means as well — licensing requirements, standards organizations, and market incentives. Additionally CMS and insurance companies will undoubtedly play a major important role.

As discussed before, AI constitutes a new way of encoding medical knowledge. Panch et al. put it this way:

“.. the correct paradigm for analyzing clinical AI should be is as encoded clinical knowledge, rather than considering it as a product such as a pharmaceutical or medical device.” - Panch et al., pg 5.

Additionally, the use of AI constitutes a new form of medical practice, which the FDA is not allowed to regulate.

The question then is what, if any, role the FDA should play. Here’s what Panch et al. say:

“Centralized regulation would only be required for the highest risk tasks—those for which inference is entirely automated without clinician review, have a high potential to negatively impact the health of patients, or that are to be applied at national scale by design, for example in national screening programs” - Panch et al. pg 3.

I think this strikes a good balance. Today the FDA regulates AI using a tiered approach based on what they perceive as the risk for the intended use case. Software that is intended for high risk applications (like diagnosis) has more strict requirements than software intended for lower risk things (such as medical image processing).9 Very low risk systems (such as systems for searching through medical records or systems that suggest billing codes) don’t require FDA approval at all. Ultimately we may want to shift the dividing line between what does and doesn’t need FDA approval to only cover only narrow-purpose systems intended for very high risk use cases. As discussed above general purpose AIs should be treated like doctors, not medical devices.

Note (added shortly after publication): The only thing I would add is that a postmarket FDA approval is probably a good option to maintain given the centrality of the FDA in the current healthcare system. Of course in theory private organizations could emerge to do it too, similar to Underwriter’s Laboratory (UL).

Such a shift in how the FDA regulates AI would eliminate a central point of control over medical practice, respect people’s first amendment rights, and incentivize a broader shift towards superior methods of decentralized regulation and oversight.

How to bring about the necessary shift from a centralized to a more decentralized system is a very open question. Right now the FDA is slowly moving towards new procedures for regulating general purpose AI. It’s not clear how well they can handle the challenge and in any case relying on an FDA stamp to solve all problems would be a major mistake. Ultimately it’s quite likely that congressional action will be needed.

Thank you to Steve Gadd and Ben Ballweg for proofreading this.

Panch, Trishan, et al. “A Distributed Approach to the Regulation of Clinical AI.” PLOS Digital Health, edited by Henry Horng-Shing Lu, vol. 1, no. 5, May 2022, p. e0000040. [PDF]

For AI devices that are intended to detect or diagnose disease, they require that they operate at a similar sensitivity and specificity as an average radiologist on a test set. For systems that are used for triage or image processing, the requirements are somewhat lower. The exact requirements are in a constant state of flux, so companies generally employ or contract with regulatory consultants to help understand the current state of things at the FDA.

Hammond, Alessandro, et al. “An Extension to the FDA Approval Process Is Needed to Achieve AI Equity.” Nature Machine Intelligence, vol. 5, no. 2, Feb. 2023, pp. 96–97.

Some of these are simple low risk tools for image segmentation that could help clinicians (see footnote 9 also). There are also systems that tag all possible lesions in CT scans, helping radiologists miss less things. Hospitals seem to think that FDA approval is required before systems developed in academia can be used clinically. This is a legal grey area as I discuss in the post - most likely its fine since the academics aren’t selling anything but it’s not entirely clear.

Similarly, it’s generally thought that FDA approval is not required to sell “create your own DIY vaccine” kits.

Green, Robert C., and Nita A. Farahany. “Regulation: The FDA Is Overcautious on Consumer Genomics.” Nature, vol. 505, no. 7483, Jan. 2014, pp. 286–87.

The FDA can and has shut down medical practices which cause direct harm like trepanning, giving people mercury, and bloodletting. The FDA’s authority to do so is very clear however, and in many cases tort law and local state laws can do the job. I lean towards banning practices such as homeopathy which cause indirect harm by fraudulently bilking people out of funds that might have been used to treat whatever ailment they have. (If you thought I was a libertarian, you are very wrong!)

In April 2023 the FDA issued draft guidance on how to companies can create a pre-registered change control plan that will allow post-approval updates to AI. How well it works and how much burden it entails remains to be seen. Ideally in the future AI systems will be able to engage in lifelong learning just as doctors do. The current FDA system is still quite far from allowing that.

Another example of a potentially low risk use is image segmentation (coloring all the pixels of a given structure, like a kidney stone or tumor). Segmentation is laborsome to do manually but easy to check if its done right. This is super easy for AI to do, for instance Meta’s FAST tool can segment arbitrary structures in medical images very well even though it wasn’t specifically trained for that purpose. Using AI for segmentation is very low risk if a radiologist is always checking the result. FDA approval is required for all segmentation algorithms currently.

I think you're missing part of the story here. Insurance companies rely on FDA approvals to decide what "medical devices" they will reimburse. FDA doesn't touch anything that doesn't make specific health claims, so patient facing chatbots come with no guarantees but also can't charge a lot because of this. The top AI companies are fine with the current setup because they'll get the approvals and regulatory barriers will prevent competitors from making any real money.

Strong work here, Dan. It seems like we're at a "damned if you do, damned if you don't" phase for regulating AI in medicine. The last thing we want to do is throw out the baby with the bathwater, and yet we have a strong obligation to prevent horrible things from happening.

I think they're going to happen, and we're going to deal with them and learn from them, but it's going to be really ugly for a few transitional years. I love the idea of having a dedicated "clinical AI" type department, and I do see this happening, but not right away. The interim is going to be very chaotic.