Why yeast-based vaccines could be huge for biosecurity

or, "Beers for Biodefense"

Vaccines can be distributed as a food. That’s the radical implication of the work of Chris Buck, a scientist at the National Cancer Institute. This December, Chris consumed a beer he brewed in his home kitchen using genetically modified yeast. A few weeks later, a blood test showed a significant concentration of antibodies against a strain of BK polyomavirus (BKV), where previously he had none. His discovery flies in the face of much conventional thinking about oral vaccines.

Now, Buck thinks he can create yeast-based vaccines for a variety of viral diseases. If his vision pans out, you might be drinking a beer or eating yeast chips to protect yourself during the next outbreak. Moreover, you may be doing so just weeks after the outbreak starts, rather than waiting months or years for drug-approval processes to play out. The regulations around food-grade genetically modified yeast are much easier to navigate than the regulations around vaccines and other drug products.

While Buck’s feat might have the appearance of a gonzo biohacking experiment, it is actually the culmination of about fifteen years of work.

What is BK polyomavirus (BKV)?

For most people, BKV isn’t thought to cause noticeable symptoms. It might cause bladder cancer in some people. Most people have been infected with the virus by age seven, and it is estimated that at least 80% of people carry either a semi-active or latent form of the virus.1

Usually the immune system keeps the virus in check so it isn’t a problem. However, the virus can wreak havoc on those who are immunocompromised, such as kidney transplant recipients, who have their immune systems artificially suppressed. (For years Buck has had people on transplant waitlists emailing him begging him for a vaccine.) Polyomavirus has also been implicated in a common condition called painful bladder syndrome, although a direct causal connection hasn’t been conclusively established.

The first BKV vaccine

Buck’s lab helped discover five of the fourteen polyomaviruses known to infect humans. They also helped show that the outer coat protein of the virus is highly immunogenic when assembled into icosahedral shells. Over the past few years they have done evaluations of an injectable polyomavirus vaccine in monkeys and yeast-based polyomavirus vaccines in mice.

The first vaccine consisted of BKV’s outer coat protein as the immunogen, which assembles into icosahedral shells that are called “virus-like particles”. When injected intramuscularly into rhesus monkeys, the vaccine caused antibody levels to shoot up to a level that is believed to confer strong protection against kidney damage in transplant recipients. Antibody levels remained high for the duration of the study, which was two years.

Unfortunately, scaling up the production and purification of viral coat proteins is complex and expensive. The vaccine technology was successfully licensed to an industry partner in 2019 but human clinical trials have not yet been announced, suggesting the development of clinical-grade material has been challenging. This motivated Buck to explore whether the particles could be produced more cheaply using genetically engineered baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae).

Their initial tests looked at the effects of ground-up yeast sprayed into mice’s noses and scratched into their skin. The ground-up yeast delivered via these routes worked, but not as well as injecting the purified particles.

The big surprise

Polyomaviruses are primarily found in the urinary tract, not the gut. So nobody expected an oral vaccine to work, but they decided to give it a try anyway for completeness. During their first pass they fed the mice ground-up yeast, which didn’t work at all.

They then tried feeding the mice intact live yeast, mixed in with their food. To their surprise, this method elicited an antibody response. Live yeast sprayed in the nose did not elicit a response, but those consumed did.

Once in the gut, it appears that the yeast start to degrade and release the empty viral shells to trigger an immune response.2

These initial results were so shocking, they repeated the experiment several times. Buck has homebrewed beer off and on for decades, so it seemed to him as though an obvious next step for the project would be using the VP1 yeast to brew beer and then test that on himself.

Self-experimentation isn’t allowed at NIH?!

Buck submitted an Institutional Review Board (IRB) proposal to gain permission to bring home the yeast and then use them to brew beer for his own consumption. To his surprise, an institutional bioethics committee withdrew the proposal from the submission portal before it could even be considered by the IRB. The committee argued that self-experimentation is strictly forbidden. Buck says he can find no written policies to that effect. The committee also argued that Buck could not eat the yeast strain unless it was first registered with the FDA as an Investigational New Drug.3 The committee rejected the fact that yeast - including GMO strains - qualify as a food product under federal law.

According to Buck, the NIH bioethics committee’s view that self-experimentation is forbidden is false. Long before the beer self-experiment, Buck had sought and received IRB permission to collect a drop of his own blood for use in the lab under a protocol entitled, “Investigator Self-Collection of Blood Via Finger Prick for Use in Hemagglutination Assays.” No one can find any NIH regulation that forbids self-experimentation.

The self-experiment

Rather than continuing to fight the bioethics committee, Buck went to his home kitchen instead. Buck says he was inspired by the longstanding tradition of self-experimentation in biomedicine, including the relatively recent activities of the Rapid Deployment Vaccine Collaborative (Radvac) (NOTE: I currently work for Radvac on an AI-based antivirals project).4 Radvac was launched by veteran scientists in the earliest days of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic for the purpose of creating and self-administering vaccines using relatively simple existing technologies.

Continuing this tradition and using his personal resources in his free time, Buck set up a miniature molecular biology lab, ordered synthesis of the needed plasmid DNA, transformed it into yeast, and brewed the world’s first batch of vaccine beer. In honor of his Lithuanian collaborators who shared the BKV VP1 yeast with his lab, he chose a farmhouse strain from Pakruojis, Lithuania.

He began consuming his batch as soon as he saw green fluorescence in the suspended yeast cells (this was an indicator for the production of the BKV VP1 immunogen). Buck says that the beer was among the most delicious homebrews he’s ever made.

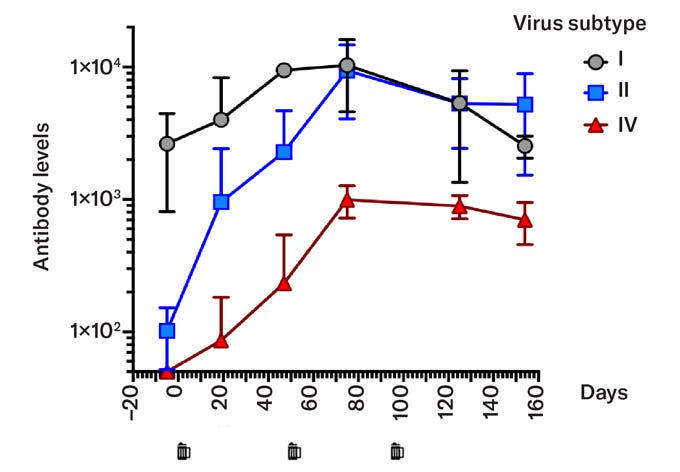

The above figure shows the result of Buck’s experiment. Prior to consuming the beer, Buck had antibodies for BKV type I but not Type II or IV. The vaccine contained shell protein from BKV Type IV, but resulted in the production of antibodies that neutralized both type II and IV.

Previous oral vaccines

Oral vaccines are not new. A letter from 1768 describes how people living in or near modern-day India sometimes employed an oral method of smallpox variolation as a less painful alternative to scratching dried smallpox scabs into the skin. While the skin-scratching method was thought to be superior, the oral method was sometimes used with pain-averse children and was found to “produce the same effect”. A small amount of dried smallpox scabs were simply mixed with sugar and swallowed by the child.

The first widely used oral vaccine appeared for poliovirus in the mid 1950s, and it consisted of a live weakened form of the virus. Polio naturally infects the lining of the intestines, so an oral vaccine made good sense. The FDA has also approved vaccines for typhoid, cholera, rotavirus, and adenovirus types 4 and 7.5

Oral tolerance and other challenges

Despite the notable successes covered in the last section, oral vaccines face big challenges - they must survive the harsh environment of the stomach and then trigger an immune response from within the gut. The immune system has evolved not to respond strongly to novel substances found in food - otherwise you’d get a massive amount of inflammation every time you tried a new food. When a novel substance is consumed, the immune system looks for danger signals like inflammation. If none are detected, regulatory T cells may be created that actually dampen any immune response to that substance.

The current thinking in immunology is that oral vaccines must trigger an initial inflammatory response, otherwise they risk triggering tolerance to viral antigens - the exact opposite of what they are intended to do. They also must do this while keeping side effects within a manageable range. Current oral vaccines are known for side effects like abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea.

Given all this, one may wonder why the yeast vaccine stimulated an immune response and didn’t induce tolerance. While baker’s yeast is harmless, polysaccharides on the cell wall of yeast can stimulate an immune response in some situations, and that might be what’s happening here. Buck has a hypothesis that the VP1 immunogen binds to immune presentation cells in the small intestine called M cells, which trigger an immune cascade leading to antibody production. Both the cholera toxin subunit used in the Dukoral oral cholera vaccine and BKV VP1 particles bind to gangliosides which are known to be present on the surface of intestinal M cells.

Implications for medical research

Yeast-based vaccines open up interesting avenues for research. For instance, painful bladder syndrome, which affects about 0.5% of people in the United States, is associated with high-level shedding of BKV in the urine (or its close relative JC polyomavirus). Unfortunately, the association doesn’t conclusively prove that polyomaviruses cause painful bladder syndrome, and pharmaceutical companies are unlikely to try to develop a vaccine to prevent or cure painful bladder syndrome unless a causal link has been demonstrated. In lieu of that, people with painful bladder syndrome could consume yeast-based products designed to enhance their immune system’s response against BKV and then see if the bladder pain goes away.

In a recent video, Buck mentions that polyomavirus has been found in the brain in rare cases, which he argues makes it a possible suspect in the etiology of Alzheimer’s disease. With nearly everyone already infected with polyomavirus, establishing a link between the virus and Alzheimer’s or bladder cancer is very challenging. Now, people can consume a polyomavirus vaccine early in life, and long-term follow-up can look to see if there is any reduction in Alzheimer’s or bladder cancer relative to a matched control group that didn’t consume that vaccine.

Yeast-based vaccines should reduce vaccine hesitancy

There is a strong theoretical case that yeast-based vaccines should reduce vaccine hesitancy. For one thing, lipid nanoparticles, mRNA, and viral vectors sound scary and exotic, while yeast is a familiar constituent of beer and sourdough bread.

As discussed above, there has not been a need so far to add adjuvants, which are compounds that are often added to vaccines to stimulate an immune response. Adjuvant compounds like aluminum salts and thimerosal have previously raised the hackles of vaccine skeptics.

Most notably, between 20-30% of adults have a strong fear of needles, and a systematic review estimated that around 20% of people avoid getting the flu vaccine simply due to needle fear. Needle fear is tied into a universal human cognitive bias called the horn effect. Simply put, the horn effect principle says that when a scary thing regularly co-occurs with a harmless thing, the harmless thing becomes scary. One may argue that needles, as sharp objects, are inherently scary, creating an obvious horn effect around vaccination. But there is also a horn effect around needles themselves. Alex Tabarrok points out that needles often appear in the context of serious illness inside hospitals, and thus are associated with “serious medicine” – scary stuff. Thus, it’s not surprising that psychologists think that much of vaccine hesitancy is driven by needle fear. It’s interesting that pills are readily consumed under a doctor’s recommendation, even though the substances they contain are often far more dangerous than vaccines.

Naturally, we can expect many people will be cautious when it comes to consuming a “beer vaccine”, especially if it hasn’t gone through large scale clinical trials. However, as a growing number of people create and consume yeast-based vaccines, confidence in them will grow.

While large, well-conducted randomized Phase III trials are essential for accurately quantifying effectiveness, the FDA’s requirements for lengthy Phase III trials before people are allowed to take a vaccine makes vaccines look scary. As Buck told Futurism news: “Our response for the past half century has been to imagine that we can rebuild public trust in vaccines with displays of increasingly stringent FDA approval standards. This approach backfired. Imagine if I set out to do safety testing on a banana, and I dressed up in a hazmat suit and handled the banana with tongs… you’d think: ‘wow, it looks like bananas might be about as safe as nuclear waste’.”

Implications for pandemic preparedness

Buck believes it is likely possible to create yeast-based vaccines for bird flu or SARS-CoV-2. This is a somewhat bold claim, but it’s well worth considering the implications for biosecurity.

Current SARS-CoV-2 vaccines help prevent hospitalization and death, but are highly suboptimal as they do a very poor job of preventing infection. This is because they mainly induce systemic immunity (IgG antibodies) but do a poorer job of inducing mucosal immunity (IgA antibodies). IgA antibodies secreted in mucus can provide a critical “first line of defense” against a virus right where it is most likely to enter the body - the nasal passageway.

A strategy that could be explored with yeast-based vaccines is called “prime and spike”. This consists of using an adjuvanted injectable vaccine followed by an unadjuvanted nasal vaccine. Roughly speaking, the injectable vaccine stimulates systemic immunity while the nasal vaccine stimulates mucosal immunity. A yeast-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine sprayed in the nose of someone who has already taken an injectable SARS-CoV-2 vaccine could induce robust mucosal immunity throughout the nasal passage, potentially reducing infection risk dramatically.

During a pandemic, yeast could be distributed rapidly in a decentralized manner via two complementary form factors - dried yeast chips and beer.6 The dried yeast could be eaten either as chips or crackers or packed into (possibly enteric) capsules.

An advantage of beer is that every microbrewery in the country is equipped to produce it in bulk. Buck has already spoken with breweries that are interested in brewing vaccine beers, and there are many kidney transplant patients interested in consuming them. Given the positive response Buck has gotten already to his vaccine beer for the relatively obscure polyomavirus, during a pandemic it’s easy to imagine many microbreweries would want to make vaccine beer available in their community, and that many people would be interested in consuming them.

Although most standard beers are fermented for at a week to allow the flavor to mature, Buck says that Scandinavian and Baltic farmhouse styles are designed to be consumed within a few days of brewing. The production of dried yeast “chips” is faster than beer production, but not radically so. Starting from a small amount of yeast, growing enough yeast to create a batch of chips would likely take a few days. Next, the yeast needs to be air-dried or loaded into a food dehydrator at low temperature. This typically takes another day or so. Research shows that yeast-based vaccines can remain shelf stable for a year or longer.

Animals can be vaccinated easily en masse — farmers can respond to bird flu simply by sprinkling the yeast in feedstock.7 Recently, the USDA invested 2.5M in yeast-based vaccines that display the hemagglutinin protein found on three H5N1 strains of the avian flu.

Obviously the biggest win here is the ability to produce vaccines in a decentralized manner and start distributing them to people in weeks rather than waiting for EUAs from the FDA, which we saw were very slow or never happened during the pandemic. Clinical trials to study safety and effectiveness would be held in parallel. Selling GMO yeast is legal in the US as long as the products are not labeled or promoted as treating any particular disease. Yeast vaccines could be sold for “boosting the immune system”, a general-purpose claim already found on many products. For more on how to sell GMO yeast legally as a Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) food product, see this post.

A notable precedent is Lumina Probiotic, a GMO bacteria that does not produce lactic acid, which is responsible for tooth decay, cavities, and bad breath. It is completely legal to sell as long as it is not sold for preventing cavities. Another precedent is the company Evolv, which sells a supplement containing GMO yeast that expresses a GLP-1-like peptide. I can’t help but also mention ZBiotics, which sells a GMO probiotic bacteria that’s been modified to produce an enzyme similar to the one your liver uses to process ethanol.

What’s next?

Currently Buck is planning Phase I human trials of the BKV vaccine, and starting research into yeast-based vaccines for the flu, COVID-19, and adenovirus.

Chris’s brother has started Remy LLC, a company chartered to sell food-grade GMO yeast products.

Radvac, where I work on AI for antiviral repurposing, has just started a new research program focused on yeast-based vaccines.

Thank you to Chris Buck for providing extensive comments on an early draft of this piece, and to Preston Estep for proofreading.

Further reading:

80 minute interview with Chris Buck on food-based vaccines and related topics

21 minute roundtable discussion: “Food-based vaccine revolution”

“Binghamton University researcher to lead $2.5 million project to create better avian flu vaccine”

2021 Scientific Reports paper: “High immune efficacy against different avian influenza H5N1 viruses due to oral administration of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based vaccine in chickens”

2024 Frontiers in Immunology paper: “Saccharomyces cerevisiae oral immunization in mice using multi-antigen of the African swine fever virus elicits a robust immune response”

2025 Microbial Cell Factories paper: “Cell surface display of VP1 of foot-and-mouth disease virus on Saccharomyces cerevisiae”

Footnotes

Buck says that in his own surveys, about 90% of people have antibodies for BKV which is in line with existing research. In the remaining 10%, Buck hypothesizes that those people may have been infected but with a low-grade fever that was never fulminant enough to elicit an antibody response.

This is consistent with work from 2023 which showed that yeast genetically engineered to produce a GLP-1-like peptide can survive long enough to produce significant quantities of the peptide in the intestinal tract of mice.

Registering compounds being studied in humans as INDs is a standard practice at NIH to ensure that clinical trials are done in compliance with the FDA’s strict regulations. Registering as an IND also helps with intellectual property claims. However, Buck did not want to register the yeast as an IND not only because of the paperwork involved but also because if the FDA grants an IND for a food/supplement, then it usually ceases to be a food/supplement and becomes a drug in the FDA’s eyes. Given the stakes, Buck was not willing to take that risk, and rightly so.

Another famous self-experiment was Barry Marshall’s consumption of helicobacter pylori to prove that the bacteria cause stomach ulcers. In the 1950s, Jonas Salk vaccinated himself, his wife, and his children to prove the safety and efficacy of his inactivated polio vaccine before clinical trials. Scientists are the ones who best know the risks of what they are undertaking and those who are willing to take risks for a good cause should be lauded for doing so. Banning scientists from participating in their own research is not that different from banning firefighters from running into a burning building.

The typhoid vaccine consists of live attenuated typhoid bacteria and was approved by the FDA in 1989. The cholera vaccine Vaxchora was approved by the FDA 2016 and contains live but attenuated cholera bacteria. Another cholera vaccine used internationally, Dukoral, uses killed cholera bacteria plus a recombinant cholera toxin B subunit. The FDA has approved two oral vaccines for rotavirus which consist of live but weakened virus. The Army gives new recruits a vaccine against Adenovirus Types 4 and 7 which consists of live virus. Interestingly, the Army’s vaccine consists of live virus in enteric-coated tablets. The adenovirus infects the intestinal lining. However, since the virus is more “at home” in the respiratory tract than the intestinal lining, the illness is much less severe. Still, the vaccine is known to make people feel sick for a few days. Buck has thought about offering Army recruits a yeast-based vaccine for adenovirus and then monitoring them to see if it prevents them getting ill when taking the standard live adenovirus vaccine.

An important exception here is the EU, where cultivating GMO yeast is illegal unless authorized by regulatory authorities. GMO foods are generally banned in the EU, and so far it does not appear the EU has legalized any GMO yeast strain. This is in stark contrast to the US, where a variety of GMO yeast strains are popular among American brewers. (The most popular strain produces lactic acid, a souring agent, and there are others that produce fruity flavors). These GMO yeast strains are illegal to cultivate in the EU, even for personal consumption.

Buck points out that many breweries and distillers routinely donate the spent grain from the fermentation tanks to farmers so they can use it as chicken or cattle feed. If a distiller were to use a version of their usual yeast strain that expresses a vaccine immunogen, the livestock vaccination process would become an automatic free byproduct of the existing supply chain.

Was the beer delicious?

Thank you for telling Chris's story, Dan! I hope this technology goes as far as it can –– it is much needed