A critical analysis of Microsoft's quantum "breakthrough"

A friend of mine requested I write something about Microsoft’s recently announced quantum chip, building off my last two posts on quantum computing. I’m finding these articles on physics-related topics relatively easy to write, so I’m happy to oblige.

More generally, critiquing “breakthroughs” like this is in line with two core focus areas of this blog/newsletter — scitech progress and metascience.

There’s an interesting saga here. Claims similar Microsoft’s have been made before. Those claims were published in major journals like Science and Nature but later retracted. There was evidence of sloppy data handling, confirmation bias, and selective reporting of data. While no explicit fraud has been proven, the saga has resonances with previous articles I have done on pathological water science, the history of fraud in Alzheimers’ research, the drug Cerebrolysin, and LK-99.

What did Microsoft announce?

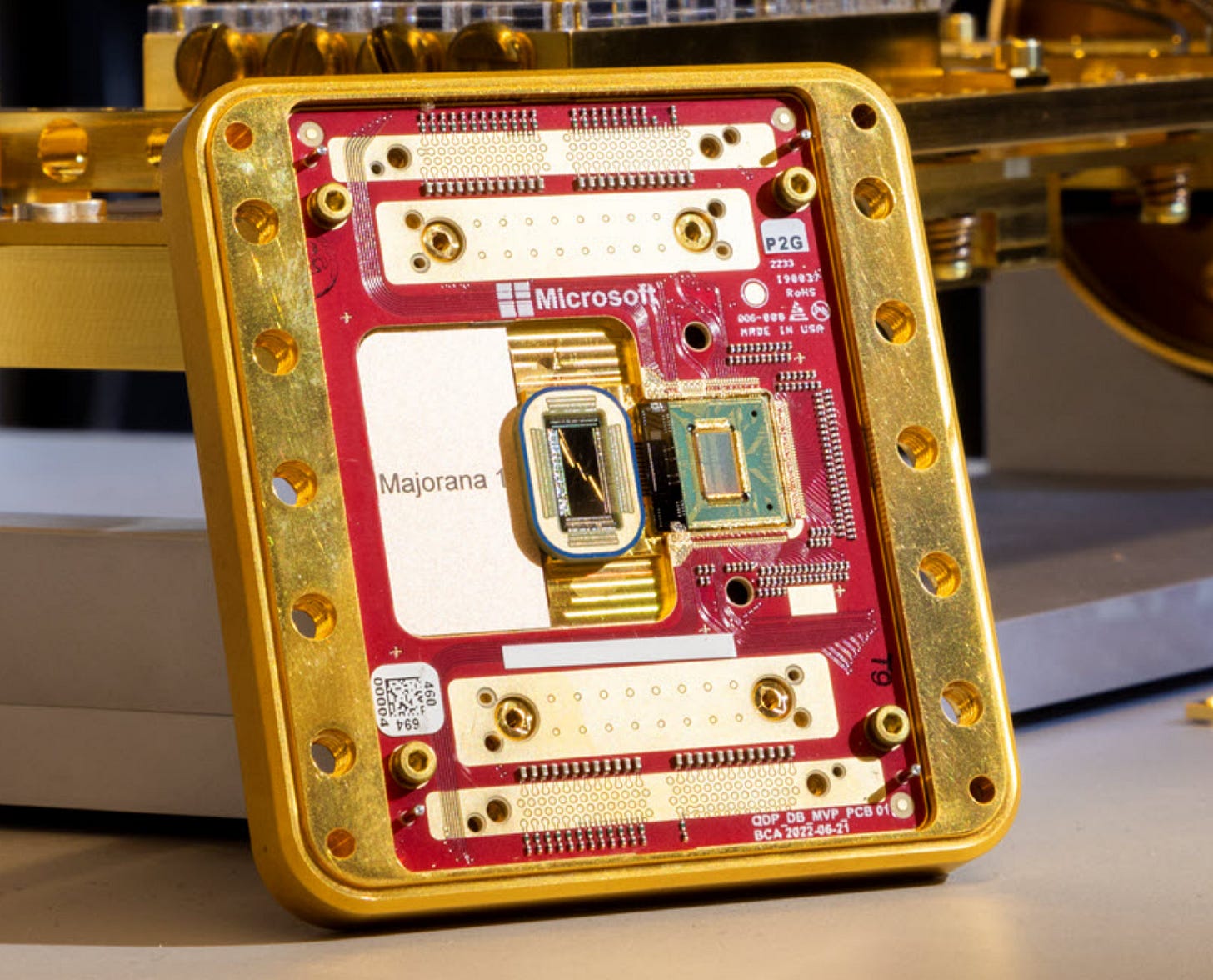

On February 17th, Microsoft published a 23 page “roadmap to fault-tolerant quantum computation” paper on arXiv. Two days later they announced the “Majorana 1”, a “quantum chip” powered by a “Topological Core.” The chip is very impressive looking:

The announcement was carefully orchestrated for maximum effect. The media blitz consisted of a Nature paper, a press release, a high production value video, and a laudatory New York Times article by Cade Metz, all of which dropped within hours of each other.

The second sentence of their press release contains the core claim regarding the chip:

“It leverages the world’s first topoconductor, a breakthrough type of material which can observe and control Majorana particles to produce more reliable and scalable qubits, which are the building blocks for quantum computers.”

The press release claims each chip has eight topological qubits:

“Today, the company has placed eight topological qubits on a chip designed to scale to one million.”

I think many have assumed that the Nature paper gives evidence for these topological qubits. Nope! It only presents evidence for Majorana particles. Furthermore, many physicists are skeptical of the paper’s claim to have created Majorana particles. There has been a history of similar claims before that haven’t panned out, including several retracted papers.

Note - in the next two sections I try to explain some of the physics, because I find it interesting… but this stuff is quite tricky to understand! If you’re more interested in the backstory and metascience, skip ahead.

What are Majorana particles?

One of the key things I learned from reading Richard Feynman during my physics days is there are profound benefits to trying to understand first principles yourself. So, I’ll try to explain some of the first principles here as well. Unfortunately, it’s difficult, but even a rough picture is better than none.

Majorana particles have been one of the most elusive in all of physics. In the 1930s physicists realized that particles in our universe are one of two types — fermions or bosons. Fermions have half-integer spin, while bosons have integer spin (“spin” refers to the particle’s intrinsic angular momentum). For instance, the humble electron is a fermion with a spin of 1/2, while the photon is a boson with a spin of 1. Quantum field theory predicts that fermions have anti-particles while bosons do not. The theory further predicts that two fermions cannot inhabit the same quantum state (the “Pauli exclusion principle”), but two bosons can.

In 1937 Ettore Majorana hypothesized that there might exist a third class of particle that are their own antiparticle. It was a purely theoretical idea.

In 1982 Frank Wilczek showed that the mathematics of quantum field theory indicate that if the universe was two dimensional, the distinction between fermions and bosons would break down. In two dimensions, when particles are swapped they exhibit any phase change, resulting in special statistical properties. For this reason, he called such particles “anyons.” They can also have any spin, whereas in 3D particles are forced to have either integer or half-integer spin.

Majorana particles are a special type of theoretical anyon with spin 1/2 and “non-Abelian” character, a mathematical property. Some physicists think that neutrinos might be Majorana particles living in 3D, but this is a minority view.1

Wilczek also proposed that there might be quasiparticles in condensed matter systems (materials) that are anyons. Just as a particle is a quantum excitation of a field, a quasiparticle is a quantum excitation of a material. Quasiparticles can sometimes be conceptualized as localized vibrational modes in a material with quantum properties (discrete energy and angular momentum). Other times, however, they are nonlocal - spread out over multiple locations at once. Majorana quasiparticles are predicted to have this nonlocal character.

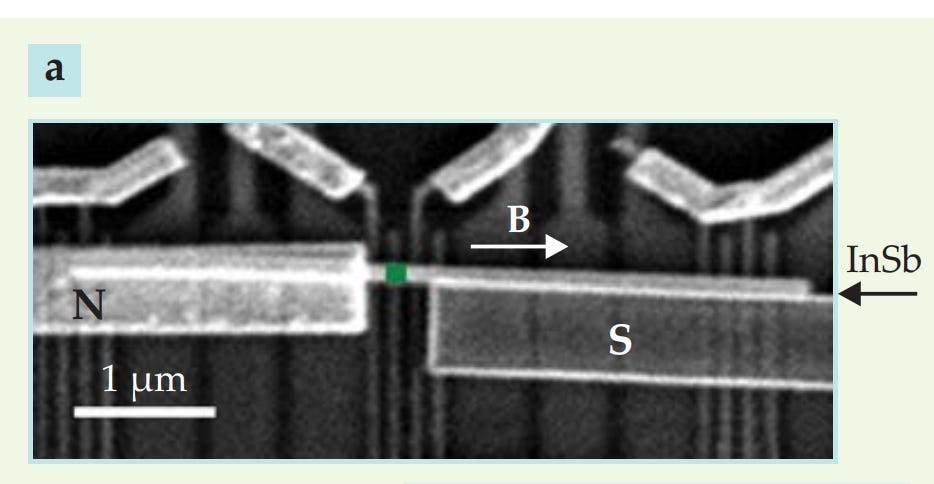

In 2012, it was claimed that a Majorana quasiparticle was created in a piece of semiconducting wire in a magnetic field. The wire spans a normal conductor and a superconductor:

This quasiparticle is claimed to be nonlocal - inhabiting two parts of the wire at once.

Furthermore, this quasiparticle is predicted to have a spin of 1/2, but with zero charge, zero mass, zero non-spin angular momentum, and zero energy. So, you might wonder — how do we even know they are there? Well, physicists argue that their presence affects the relation between current and voltage through the device. Since the presence of these “ghost” quasiparticles is being inferred indirectly, it’s possible the observed data could be due to other phenomena happening in the device. Several times physicists have presented evidence for Majorana particles, but then other physicists have discovered other “look alike” phenomena that can explain the same data.

What is a topological qubit?

In this section, I’ll attempt to explain what a topological qubit is and how it is constructed from Majorana quasiparticles. I have not seen any recent article make any serious attempt at explaining this stuff for a lay audience. There’s a good reason for this — understanding Majorana quasiparticles requires understanding three areas of physics at an advanced level - condensed matter theory, quantum field theory, and relativistic electromagnetism. When I took a class in quantum computation in 2012, there were a couple lectures on topological qubits, but I couldn’t fully grok the material. I didn’t understand things completely then, and certainly don’t understand things now.

Still, I think I can paint a rough impression of what’s going on — or rather, what is supposed to be going on.

Electrons play a big role here. Electrons can be conceptualized as tiny spinning charges. That spin means the electron creates its own magnetic field. When an external magnetic field is applied to a system of moving electrons, the electrons start to move in circular paths. When an electron moves in a circular path, it starts to interact with its own spin due to relativistic effects. When very high fields are applied, the spins of the electrons get “pinned” in particular directions. This creates what physicists call “spin texture” in the material. This pinning phenomenon helps make the Majorana quasiparticles more robust, and it sets the scene for a phenomena physicists call “braiding.”

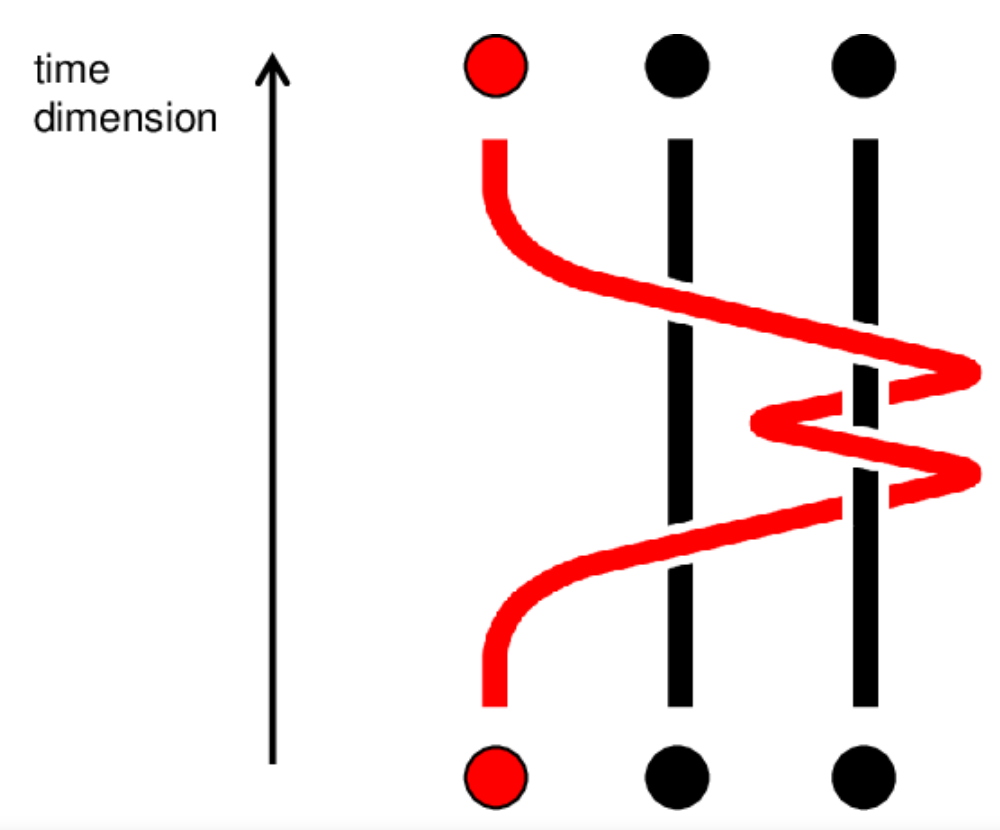

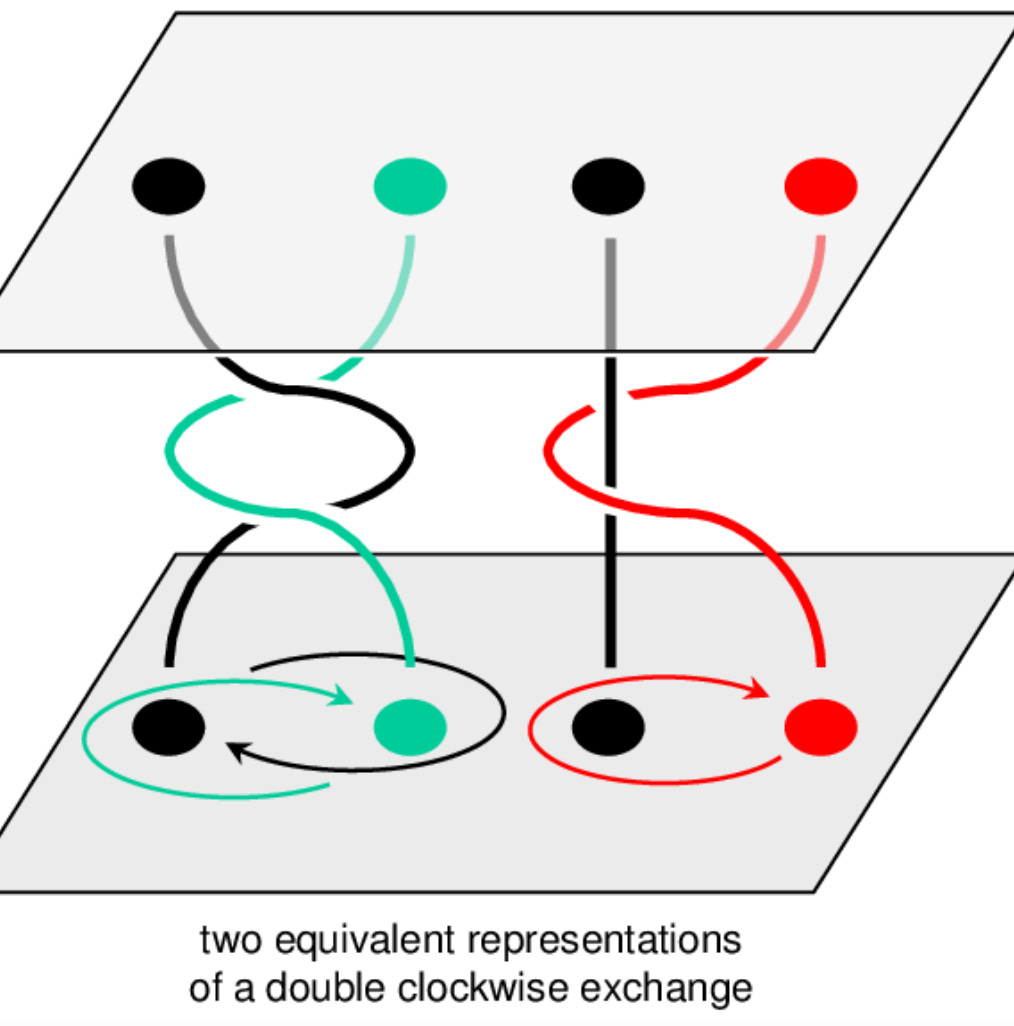

If one Majorana quasiparticle are revolved around another in a very high magnetic field, what happens is conceptually similar to rotating one rope around another, or equivalently, twisting two ropes around each other:

The twisting of two ropes can be done two distinct ways - clockwise or counterclockwise. Once two ropes are twisted, they can be hard to untwist. If the ropes are twisted and the ends fixed, then they are impossible to untwist. The number of twists and the directions of those twists is said to be “topologically robust.” If you can do quantum computations by twisting “Majorana ropes”, the process should be very robust to noise.

Here’s one way of twisting three ropes:

Here are what some actual quantum computation gate operations would look like, using either four or six topological qubits:

Russian-American physicist Alexei Kitaev proposed this sort of method for robust quantum computation in 1997. Since then, research groups around the world have been attempting to realize it.

What is the history here?

Microsoft founded “Station Q” in 2006. From day one, they have focused largely on topological quantum computation. Michael Freedman, a Fields Medealist, was a founding faculty. In the early days, the research at Station Q was purely mathematical and theoretical in nature. Some physicists believed Majorana quasiparticles could exist, but it was not at all clear. It’s interesting that Microsoft funded this research given there was really no clear prospect for commercialization at the time.

In 2012, a Delft University team studied a nanowire similar to the one pictured above. They found some unexpected peaks in the conductance data which seemed to indicate Majorana quasiparticles. Microsoft got really interested, and started investing money in to the Delft University group and other experimental groups at the Niels Bohr Institute and the University of Sydney.

In 2014 a Princeton University team presented evidence for “Majorana states” around iron atoms in a superconductor. Around this time, physicists found other explanations for the data presented by the Delft and Princeton teams. I think it’s fair to say most physicists did not believe the claims.

Retraction #1

A 2017 Science paper by researchers from Tsinghua University reported “chiral” Majorana quasiparticles in a superconducting quantum Hall device. Researchers at Princeton and Purdue tried to reproduce their claims, but were not able to. Frustrated physicists started to scrutinize the data in the original paper, and they started finding irregularities. Under pressure, the Tsinghua University researchers conducted an internal review of their data. In 2022, five years after the original paper, the Tsinghua researchers requested their paper be retracted and Science quickly obliged their request. The authors admitted that in their rush to publish, mistakes had been made. It turns out their devices were extremely sensitive to external noise, leading to extreme irregularities in their data. The researchers hastily jumped to a conclusion without considering other explanations. The saga is said to have hurt the reputation of Tsinghua University.

Retraction #2

In 2018, a Microsoft-supported group at Delft University published a paper in Nature, which again claimed to have created Majorana quasiparticles in a nanowire. This time, the data was more convincing, and it was quickly hailed as a breakthrough. Over time, however, physicists started to notice inconsistencies in the data. Serious concerns came to light in 2020. Those concerns ultimately caused Nature to retract the paper in 2021. As a result, Delft University commissioned a team of independent experts to determine if any wrongdoing took place. The team found that the researchers had omitted from publication data which contradicted their results — a serious failing of scientific rigor. It is unfortunately not an uncommon issue. The investigators could not find any evidence that the researchers intended to mislead, however. Instead, they attributed the failing to poor data handling practices and confirmation bias (humans’ innate bias towards focus on confirming data while disregarding non-confirming data).

Also in 2018, a team at the Chinese Academy of Sciences published a paper in Science which presented evidence for Majorana quasiparticles in an iron-based superconductor. In 2019, another Chinese team reported similar findings in Nature Physics. In 2021, an alternate explanation for the 2018 and 2019 data was found.

Expression of concern

In 2020 a team centered at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen published evidence for Majorana quasiparticles in Science. As concerns were raised, the journal requested the authors to release more of their data. Shortly after the scientists released more data, the journal slapped an “Expression of Concern” on the paper. The notice states that the “tunneling spectroscopy data published in the original paper are not representative of the entirety of the data released in association with this project.” This was yet another case of scientists selectively reporting data. The authors came out strongly against the expression of concern and stood by every claim they made in the paper. The journal requested that the Niels Bohr Institute conduct an investigation. The investigation found no evidence for wrongdoing but acknowledged “shortcomings.” Some scientists have argued that even the additional data was selectively released. In other words, the full data generated by the experiment has still not been released. If that is the case, it suggests intentional misconduct.

Did Microsoft lie about creating a topological qubit?

The Nature paper comes with this revealing comment:

“The editorial team wishes to point out that the results in this manuscript do not represent evidence for the presence of Majorana zero modes in the reported devices. The work is published for introducing a device architecture that might enable fusion experiments using future Majorana zero modes.”

No conclusive evidence of a Majorana quasiparticle is presented in the paper, only partial, controversial evidence.2 Without those particles, topological qubits cannot be formed. Yet, the press release says the chip contains eight topological qubits. What’s going on? If Microsoft has data proving the existence of even a single topological qubit, why haven’t they published it?

On Scott Aaronson’s blog, Microsoft technical fellow Chetan Nayak has given an explanation in the comments. He says that the original Nature paper was submitted almost a year ago on March 5, 2024. In the intervening time, he says that Microsoft has made significant progress. Some of that progress has been reported in a technical seminar Microsoft recently held, and more will be reported at the upcoming “March Meeting” of the America Physical Society.

I have no doubt Microsoft has made some progress in the last year. The question still remains — where’s the data?

If a topological qubit has been created, does that put Microsoft in the lead?

Nobody really knows. Quantum computing expert Scott Aaronson says he doesn’t know. It took ~20-30 years for other approaches to get from 1-5 qubits to 10-50. Nobody knows if faster progress will be made with topological qubits and if the topological qubit approach can “leapfrog” other approaches. Microsoft is the only commercial company investing substantial money into this approach. Apparently, others are not willing to bet on a “leapfrog.”

Metascience notes

This above saga highlights some ways we could do science better:

There should be a norm that announcements should be accompanied with raw data that backs up the announcement’s claims. An even stronger norm would be that groups should wait until peer reviewed publication before announcing a major breakthrough. Microsoft did neither of these things.

Journals should require that authors publish all of the data collected during their experiments, and this data should be viewable by peer reviewers during review. This will help with the problems around selective reporting that currently plague science, although it doesn’t completely solve the issue. Note that simply uploading the raw data is easy - just upload the files! What is much more time-consuming is if additional requirements are tacked on to make the data more findable, accessible, interoperatable, and reusable (“FAIR”). Simply uploading the raw data as-is is a very low bar!3

Requiring both pre-registration of experiment plans and publication of all data can go further to help with the issue of selective reporting. I don’t think pre-registration of experimental plans is done at all in physics. It probably should be, especially for areas of physics with a history of retractions and selective reporting.

Science journalism should be more skeptical and critical. Instead of merely parroting claims from press releases like Cade Metz did in the New York Times, science journalists should be critical and should explain reasons to be skeptical (like historical context, etc).

I asked Claude if it had further suggestions. Here are two suggestions it made, which I think were rather creative (and more aggressive than what I had been contemplating):

Establish cooling-off periods between journal acceptance and press releases. The current rush to publicize findings often leads to overhyped claims. A mandatory waiting period would allow for more measured communication.

Journals should adopt stronger policies against serial offenders. Fields or research groups with patterns of retracted papers should face heightened scrutiny and more rigorous review standards.

One final point:

The ~20 year quest to find Majorana quasiparticles and realize a topological qubit has an air of pathological science. In particular, the data has always been at the edge of believably, and the experiments have been plagued with confounds. The situation bares resemblance to other areas of pathological science where tremendous claims are made on the basis of noisy data lying at the edge of significance (examples: cold fusion, polywater, exclusion zone water). I think there is a better than not chance that Microsoft has made Majorana quasiparticles. However, it’s also possible they haven’t and that in 50 years this will be viewed as an episode of pathological science (I’d put a ~20% chance on that).

I want to thank ChatGPT and Claude for extensive copyediting, discussion, and fact-checking.

Neutrinos have spin 1/2, but we can’t tell if they have the statistical properties of Majorana particles. Antineutrinos exist in the Standard Model, so that seems impossible. However, some physicists believe the distinction between neutrinos and antineutrinos is only a matter of helicity (left-handed vs. right-handed states of spin/momentum) rather than them being fundamentally different particles. The matter is hard to test experimentally since neutrinos are hard to manipulate.

On Hacker News, Microsoft Research Manager Torsten Karzig made a comment about this. He says: “The Nature paper just released focuses on our technique of qubit readout. We interpret the data in terms of Majorana zero modes, and we also do our best to discuss other possible scenarios. We believe the analysis in the paper and supplemental information significantly constrains alternative explanations but cannot entirely exclude that possibility.” He also points to a 2023 paper from Microsoft that presents evidence for Majorana quasiparticles.

Of course, many scientists don’t want to upload data since they might worry competitors can use it. I think this concern might be partially ameliorated by having a license which bars others from using it without the author’s permission (??). Of course, scientists may still omit data from the “full dataset release”. They might do a subexperiment and not report ever having done it at all. Still, typically experiments have logical structure to them, and if the data is less than what is expected, that may be detected by others. My friend comments: “As much as I like the idea of "just upload the files", my #livedexperience is that this "low bar" is somehow a major obstacle. The best way to record and organize the data is often not known/contemplated at the outset of an experiment. Data collection becomes an ad hoc process. This is actually an underrated advantage of pre-registration: it forces you to think ahead and design the spreadsheets in advance.”

Dan Elton, this is a great analysis: Well written with a good explanation of the topic and why you have doubts. Elan Moritz, thank you for alerting me to Dan Elton's work.

💯✅🍀🎯 excellent exposition & solid recommendations… every five years or so I look into quantum computing and the ever fascinating battle of metaphors between google and ibm about quantum supremacy & quantum dominance… and my personal conclusions is that “there’s a pony there”, except that he’s rather tiny (right now), he’s fast asleep, and some princess has to kiss him to wake him up (too many metaphors 🤷♂️) or, maybe it’s a Schrödinger’s Pony. In any case, outstanding explanations Dan. Thank you, nice to see actual scholarship not pushing some biased POV. I truly would love to see an actual serious problem solved, not a concept for a concept of solving one.